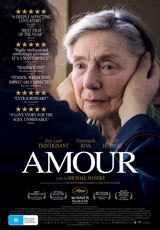

Amour begins with an audience awaiting a performance, mirroring its own audience staring back at its frames. Echoing moments of great auditorium scenes in films like Jarmusch‘s Stranger Than Paradise, Austrian writer and director Michael Haneke sets up an auspicious and yet strange opening. Sitting in the audience is Anne (Emmanuelle Riva) and her husband Georges (Jean-Louis Trintignant), awaiting the piano recital performance of a former pupil. Quickly, we move back to the couple’s apartment, where their septuagenarian life is in pleasant order. That is, until one morning when Anne spaces out over breakfast. The episode was a stroke that left her paralysed on her right side, unable to be corrected by surgery. Amour looks over the months (we assume) where Georges takes care of Anne. Their daughter (Isabelle Huppert) makes an appearance, but there is a distance that is fairly palpable from the onset, even if there is no initial animosity.

Amour begins with an audience awaiting a performance, mirroring its own audience staring back at its frames. Echoing moments of great auditorium scenes in films like Jarmusch‘s Stranger Than Paradise, Austrian writer and director Michael Haneke sets up an auspicious and yet strange opening. Sitting in the audience is Anne (Emmanuelle Riva) and her husband Georges (Jean-Louis Trintignant), awaiting the piano recital performance of a former pupil. Quickly, we move back to the couple’s apartment, where their septuagenarian life is in pleasant order. That is, until one morning when Anne spaces out over breakfast. The episode was a stroke that left her paralysed on her right side, unable to be corrected by surgery. Amour looks over the months (we assume) where Georges takes care of Anne. Their daughter (Isabelle Huppert) makes an appearance, but there is a distance that is fairly palpable from the onset, even if there is no initial animosity.

The indignities of sickness are strongly made prevalent by Haneke, where illness is experienced as humiliating, embarrassing but yet ultimately guided by ultimate love and devotion of a partner in their caregivings. Escape from sickness and disease is also a hot issue, argued easily by Anne’s deteriorated quality of life.

Typical of Haneke’s style, no musical score is present during the film, except for a few moments of classical music pieces from the piano recital, and when the former pupil comes to visit. An absence of sounds triggers an acknowledgement of the loneliness in Anne and George’s lives, and when sound does finally come, it is made pointedly clear how still their lives have become.

Emmanuelle Riva’s performance is captivating, where two women are ultimately portrayed; the healthy Anne and the sick Anne. As is in the case with many illnesses, it is the latter that stays in our minds, and Riva’s performance is truly heartbreaking as the terminally ill woman. Equally strong is Trintignant, whose performance captures the heartache and true love experienced between the couple.

Haneke’s camera sticks with his characters in the moments that fill a usual day. When Anne’s former pupil arrives to see her, he is greeted by Georges and waits in their living room. Instead of cutting to Georges fetching Anne, Haneke’s camera stays on the pupil, the perhaps less interesting of the two options. These moments of stillness belong to a style of cinema that may be slow but is still compelling, especially in moments of significant action.

Amour is a film about devotion and love so strong that it prevails in the face of life’s ultimate hardships. Though it may leave those more (emotionally) faint-hearted feeling sombre after its conclusion, the film is held together by marvellous performances and a devastatingly powerful screenplay.

Amour is in Australian cinemas from 21 February through Transmission Films.