Review by Nick Alexander, Joanna Di Mattia and Scott Halligan

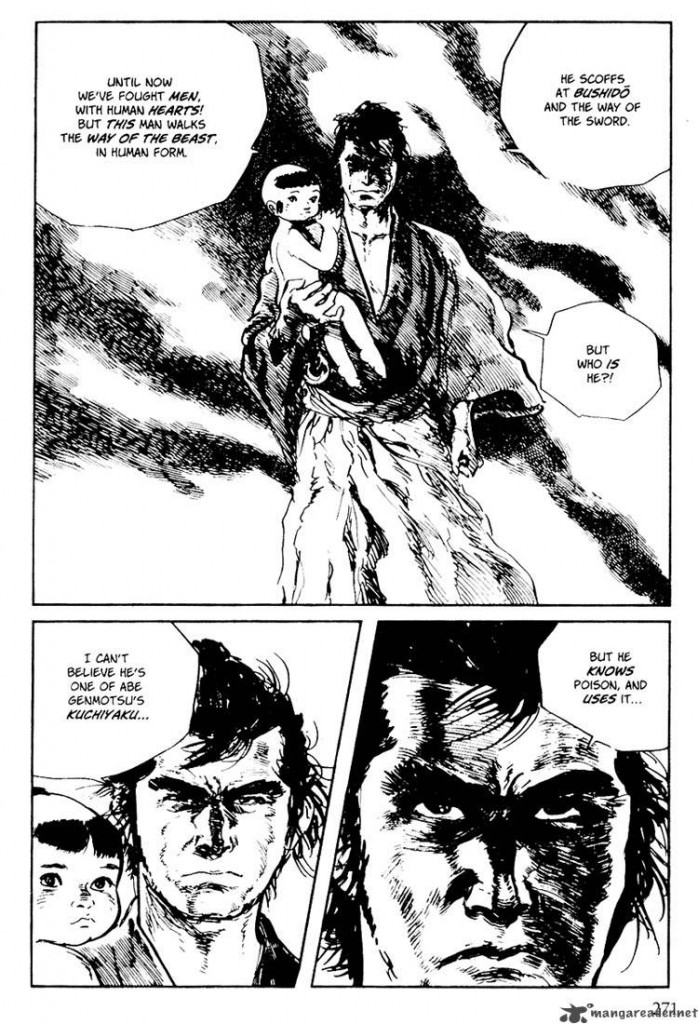

Sword of Vengeance is the first Lone Wolf and Cub film in a series produced in the early 1970s. This film introduces us to protagonist Ogami Itto (Tomisaburo Wakayama), whose job, as Second for the Shogunate, is to execute the enemies of the Shogun, should they fail to commit seppuku (ritual suicide). After his wife is murdered, Itto is framed for treason by the evil Yagyu clan (who wish to take his coveted position as Second). Now a ronin—a samurai without a master— he takes to the road working as an assassin for hire, accompanied by his young son Daigoro, who rides in a booby-trapped wooden cart. Together, they are known as Lone Wolf and Cub.

Conversation:

NICK: We’re talking about Lone Wolf and Cub, and it’s interesting because [LW&C and Lady Snowblood] were shown [at ACMI] as a double-header, and they’re both very gory films, both made in the early ‘70s. We were just talking about the way the film starts. Scott, what did you think about that dramatic opening?

SCOTT: It sets the film up to be a very gorgeously shot, deep film, with lots of seriousness and suspense, but that lasted for the remaining minutes of the opening scene. Which was extremely memorable, regardless of what happens for the remaining 75 minutes in an 80-minute film.

NICK: Well, it’s not exactly the character you would expect to be the protagonist.

SCOTT: Yeah. So it looks like he’s set up to be a villain, and then from the next scene on he’s the hero. I don’t know another film that does that.

NICK: But he’s so badly wronged that it becomes good motivation for a revenge film. His family is wiped out and double-crossed by some vague opportunistic enemy from some clan led by someone from Monkey Magic.

SCOTT: [laughs] The abominable snowman!

JO: Was he supposed to be God? I think he was in the next film as well, Lady Snowblood.

NICK: Was he Lady Snowblood?

JO: [laughing] No! He was very strange.

SCOTT: He was like a Witch Doctor or a shaman or something, but that wasn’t his character.

NICK: He seemed like a God of some kind, like more than just a clan leader.

JO: He was a blonde Jesus.

SCOTT: I loved that character. He was my favourite character.

NICK: My favourite character was the whore who got raped and murdered.

SCOTT: You say that about every film, even Schindler’s List.

***

JO: There were a lot of narrative points I actually found difficult to follow. I was finding it difficult to know who was connected to who at moments. Maybe that’s the whole point.

NICK: All that clan stuff – the Shadow Clan or whatever – it was just dropped when it moved to the bandits in what I guess was the third act.

SCOTT: The funny thing is, in the opening scene… Generally in films when you want to create sympathy for the hero or set up a feeling that this person is going to take revenge for the rest of the film, you don’t have them execute an innocent child!

JO: Which was his own child, right?

NICK: No.

JO: So who was that child!?

NICK: It was the shogun.

JO: That child was the shogun. Right. See, when thinking back about the film, I really had no idea what that was all about. It’s almost like it was a different movie.

NICK: You know in Twilight Samurai, how there was all that stuff about ‘Yogo Man’ had to kill himself because of his ties and obligations to the Shogun? So here, for reasons of honour the Shogun had to die, and so his own executioner had to kill him. But yeah, you’re right. It’s not a great way to create sympathy for the protagonist. Alright, what about the main character, Ogami Itto?

SCOTT: Where does he fit in in the pantheon of samurai heroes? One: he doesn’t have the physique of the other samurais.

JO: He doesn’t have Toshiro Mifune’s body.

NICK: Especially at the end, where he does a backflip over the pram. You know, he’s not a nimble-looking fella. And when you see him topless, you can tell he likes eggs.

JO and SCOTT: [laughing]

NICK: He actually reminded me of a Japanese Darren Lehmann. Sorry, I had to get that in there.

* * *

JO: There was a lot of humour in the film, obviously there were moments when we were all laughing. I’m interested in why the films of the ‘70s seemed to take this turn when they became things that you would laugh at. Like, you would never be laughing at Seven Samurai. Well, you would – there’s humour in that, but very different humour.

NICK: It’s used to break up the tension.

JO: You’re laughing here at the excesses of the genre. It’s like it’s taken a turn into something else.

SCOTT: Maybe we’ll talk about that more when we get to the next film (Lady Snowblood), because it was a big part of that. But how much of that humour was intentional? There are comic relief characters that the audience is supposed to laugh at, but there are also those moments where there are just comical amounts of blood. Just focusing on the guy’s facial expression – you see how serious he is – it seems like it’s supposed to be a really serious film, and then there are these completely absurd moments that may not be intended to be funny.

JO: Like the sex scene.

SCOTT: Yeah. Was that meant to be moving? It was like a walrus and a mermaid.

NICK: Well, I’ve got the comic. They’re from the ‘60s; they’re beautifully drawn, have beautiful visuals, and this film is almost shot-for-shot taken from one of the first volumes. But even in that I didn’t quite get it. You get the class thing: it’s a big deal for him to do it for her. But it’s not like they’re hitting you emotionally with it; it’s just an interesting thing, culturally.

SCOTT: I thought that the disgust that she felt was for him physically, and not because they were made to have sex in front of everybody. And then all of a sudden she was so grateful, and it was like ‘Where did that come from?’

NICK: Both films in a way are slightly – well, more than slightly – misogynistic, but she’s disgusted that he had to stoop so low because she’s such a dirty whore and her life means nothing. Okay, what about the violence, then, because it is a big part of the film. I found the blood to be so milky.

JO: Well it looked like paint. It had the consistency of a mixture of tomato sauce and milk.

NICK: One thing about the end of Yojimbo, and also Seven Samurai, is that there’s not a lot of blood. But when you see it, even though it’s in black and white it still seems much more realistic.

JO: That’s an example of that excess where the action is heightened to the point where it’s actually funny. I don’t find that that kind of violence makes me feel sick in the stomach or offends me in any way, because it’s just so hyper-real. And you see that, just to bring in Tarantino, in Kill Bill 1 where Beatrix goes to that tavern, and it’s just so excessive: it’s non-stop action and non-stop limbs and blood…

NICK: This film and Lady Snowblood, they were almost like Exploitation films, they were R-rated.

JO: Which is very much of the time, and why they felt like ‘70s movies of a particular type.

NICK: And the other thing about the samurai genre is, after Kurosawa, it moved to TV, because he couldn’t get films made post-‘60s because of the budgets, partly because of the scale he worked on but also costuming and everything. It had to move to TV where costs were cheaper. That show The Samurai was very popular in Australia. My Dad loved it. And so for that reason, for films to have a cinema release they had to have some notable element, and for both of these films it was excessive gore and violence. And tits.

SCOTT: Can we talk about the name? I found it really difficult to get over one person being called ‘Lone Wolf and Cub’. Together they’re ‘Lone Wolf and Cub’, but he’s Lone Wolf and Cub, and the kid is not even mentioned. It’s a grammatical problem that doesn’t make sense. It has to be ‘Bill’ or ‘Ben’; it’s not ‘Bill and Ben’ and the other Flowerpot Man is not even named! Let’s not put that in the transcript.

NICK: No.

* * *

NICK: Let’s talk about the little kid. He doesn’t have many lines does he? He does like the odd monkey.

SCOTT: [laughs] So, he chooses the sword over the ball – that’s his main scene isn’t it. The dad makes him choose between living a life of a human being, and living a life in Hell. They became demons after that choice, and he commits his son to it.

NICK: That was controversial.

SCOTT: There were themes of the Underworld in both of these films, Lady Snowblood as well.

NICK: What about honour? Is there honour in revenge? There’s a tough question! ‘Mike Willesee, asking the tough questions!’

JO: I’m not sure. I think that’s a very tough question.

NICK: That’s true. It is complicated. But I’m not here for a haircut! I’m here for some fucking serious discussion!

JO: I think in the context of that world, where you want to avenge the death of the murder of your wife, there is honour. But for the purposes of a film where it’s got 100 minutes to run and a number of sequels, the ‘revenge’ might be played out a bit too much.

SCOTT: I think for there to be a clear link between honour and revenge, the motivation for the revenge has to be really clear, and the hero has to be clearly good. And I think both of those lines were unclear in this film. And therefore, for the question of whether he is honourable, I don’t think the answer is clearly ‘yes’.

NICK: But what about the fact that he had a shrine and he was paying respect to the dead, and he was also just doing his job [as the executioner].

SCOTT: Those are very good points.

JO: And he has an awareness of the burden he is carrying. I don’t think he believes he has clean hands by any stretch of the imagination.

SCOTT: So that comes out about an hour into the film, after he’s already started chopping people down. Maybe he becomes honourable. I think his honourableness goes up and down because the film is just uneven like that.

NICK: Alright. Anyone get anything else to say?

SCOTT: I liked that there were monkeys in this film.

Lone Wolf and Cub: Sword of Vengeance screened as part of ACMI’s Samurai Cinema season.