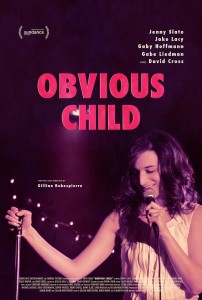

Abortions are probably not the most ideal subject matter for comedy films. But Obvious Child, directed and with a screenplay written by Gillian Robespierre, pulls it off with riotous aplomb – an assured combination of smooth direction, a hilarious screenplay and a superb breakout performance from Jenny Slate. The film manages to delight with its seamless blend of vulgar humour and surprising honesty, whilst also avoiding making a blundering political statement about abortion. Instead, it succeeds at being an off-beat quirky romantic comedy (of sorts), one that both undermines and expands the genre in subtle ways.

Abortions are probably not the most ideal subject matter for comedy films. But Obvious Child, directed and with a screenplay written by Gillian Robespierre, pulls it off with riotous aplomb – an assured combination of smooth direction, a hilarious screenplay and a superb breakout performance from Jenny Slate. The film manages to delight with its seamless blend of vulgar humour and surprising honesty, whilst also avoiding making a blundering political statement about abortion. Instead, it succeeds at being an off-beat quirky romantic comedy (of sorts), one that both undermines and expands the genre in subtle ways.

Comedian Donna (Slate) thrives on sharing embarrassing, awkward details about her personal life. Her crude, self-deprecating brand of humour is often hysterically, frank – a sampling of the unfiltered everyday musings of a twenty-something year-old woman living in Brooklyn. However, after an unexpected, brutal break-up and the eminent closure of the bookstore she works part-time at, she resorts to some heavy drinking. She meets sweet, good-intentioned Max (Jake Lacy) at a bar, culminating in a one night stand. Several weeks later she learns that she is pregnant, but only after her friend Nellie (Gaby Hoffmann) suggests that her hurting breasts may be a symptom. Donna, who openly acknowledges that she is not ready for motherhood, quickly opts for an abortion. But the sudden reappearance of her one night stand makes things complicated, and she is conflicted about her burgeoning feelings for him.

The film’s success stems firstly from its screenplay. Robespierre fills it with countless lines and moments which are some amalgamation of endearing, awkward, amusing and unexpectedly candid. This ability to direct the story on surprising little detours makes the plot consistently engaging on a scene-by-scene basis. But the screenplay’s charms cannot be isolated from Slate’s wonderful performance. She is openly aware of her character’s emotional immaturity, of the insecurities just beneath the surface, and that through her nightly comedic performances she reveals her embarrassing experiences and flaws in an open attempt to endear herself to her audiences. The supporting performances are also solidly cast and acted, but ultimately it is Slate’s show. She is so effortlessly charismatic and relatable in her layered, textured performance that you can’t help but sympathize with her.

Beyond this, the film is not interested in being too heavy-handed with its views on abortion. Robespierre is more invested in character-driven plot than politics, and more interested in endowing her female characters by a sense of autonomy than by focussing too heavily on their romantic preoccupations. Subsequently, Obvious Child gestures towards going beyond the confines of its potential classification as a, on the surface, romantic comedy, and this ultimately makes it surprising and refreshing.

Obvious Child is in Australian cinemas from 2 October through the Walt Disney Company.