In October 2012, the Pakistan Taliban shot 15-year-old Malala Yousafzai on her way home from school, targeting her because of public comments she’d made against their oppressive regime. That could have been the end of Malala’s story, but a miraculous recovery enabled her to continue her activism. Today, she is one of the world’s loudest voices on the topic of girls’ education.

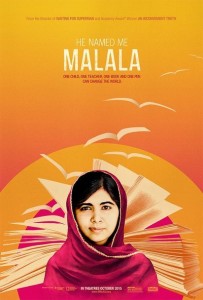

Malala’s shooting grabbed the world’s attention in 2012, while her autobiography I Am Malala sold millions of copies a year later. Davis Guggenheim’s biographical film He Named Me Malala might only add a few new elements to the narrative, but is the fitting next step.

While He Named Me Malala comes with a message, it’s more than just an activist film. Its strongest scenes are not those in which Malala is speaking in front of the United Nations, or even the moments that recount her shooting. Rather, this film is at its best when we are exposed to Malala’s youthfulness.

Before we meet Malala the brave, we meet a cheeky sister who slaps her brother across the face and likes to google handsome sportsmen. We meet a girl who struggles to connect with her English classmates, and whose school marks are a tad underwhelming for a Nobel laureate. Guggenheim could have easily used these scenes to undermine Malala’s authority, but he instead uses them to break down the mythology of Malala. Yes, she is a brilliant orator with a heroic story, but she’s no less of a school student than any other 18-year-old girl in the world.

What makes the film extra powerful is that it is narrated by Malala herself – this is very much Malala’s own motion picture – her story, told primarily in her own words. As such, the major disappointment of the film can actually be found in its title, He Named Me Malala. As opposed to Malala’s memoir, I Am Malala, Guggeinheim’s title shifts the focus towards Malala’s father, Ziauddin Yousafzai.

This isn’t to say that Ziauddin isn’t worthy of attention; he is a bold activist in his own right who is arguably the film’s second lead. But in Malala’s own words towards the end of the film, “he gave me the name Malala, but he didn’t make me Malala. I chose this life and now I must continue it”. It’s a shame that a film that is so vocal in its celebration of girls’ empowerment still finds it necessary to reference a man in its title.

Those already familiar with Malala’s story know what an inspiring individual she is. Accordingly, there’s not much Guggenheim could have done wrong in putting He Named Me Malala together. The film paints her story in a respectful light, both figuratively and literally; clever animated artworks of Pakistan help progress the narrative.

The success of Guggenheim’s film, however, should not be measured by how well it recounts her journey, or how emotional it leaves its viewers, but by how many new people become aware of Malala’s name and what she stands for as a result of this work. In the same way that his 2006 picture An Inconvenient Truth brought the threat of global warming into the mainstream, hopefully this work propels Malala to becoming a household name and the hero of every schoolgirl worldwide, if she isn’t already.

He Named Me Malala is in Australian cinemas from 12 November through 20th Century Fox.