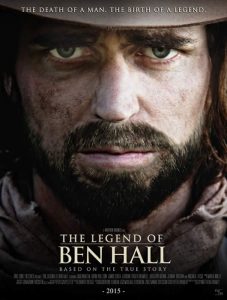

Bushranger folklore has abounded through generations of Australians, but it has usually centred on one man – Ned Kelly. After all, the first ever feature film was The Story of the Kelly Gang in 1906. In the largely crowdfunded The Legend of Ben Hall, writer and director Matthew Holmes makes his case for greater recognition of the neglected Benjamin Hall and his aptly-named gang, the Hall gang. Holmes provides us with a sometimes promising picture; ultimately failing to wholly prove his case that Hall is worthy of a place in our historical consciousness.

The film opens in 1864 with Ben Hall (Jack Martin) on the run, with most of his companions either arrested by the authorities or dead. Despite the section of prologue text telling us this, the action contained in the first act is surprisingly non-urgent. Even an early shootout sequence intended to convey the precariousness of Hall’s circumstance cannot shake the slowness of the film’s commencement. After Hall’s friend, Gordon (Andy McPhee) departs to Victoria without him, Hall teams up with John Gilbert (Jamie Coffa) and 19-year-old John Dunn (William Lee) to formally re-establish the Hall gang. The gang’s subsequent exploits – robbery, arson, and even murder – place their names on the most wanted list in the colony of New South Wales.

In his first notable cinematic role, Jack Martin is admirable as the titular character. His Ben Hall is pensive, circumspect and conflicted. Martin mostly maintains steadfast presence in his bushranger attire, but occasionally his penchant for steely seriousness can overwhelm and unnerve. Martin is mostly helpful in assisting Holmes to characterise Hall as a sympathetically lonely man caught up in the circularity of outlaw life. Almost immediately, Holmes introduces us to the fact that Hall’s ex-wife, Biddy (Joanne Dobbin), had left him for an unsightly drunk. Hall is left with no access to his son, Henry (Zane Ciarma), which expectedly causes him a great deal of grief. Despite the ostensible immorality of leading a gang, Holmes goes to great lengths to remind us that Hall never killed anyone. He even allows an old lady to keep a piece of jewellery that has sentimental value to her. Ultimately, Martin’s portrayal of Hall features a bunch of gripping moments that show us he has potential as an Australian screen performer.

The same cannot be said for his fellow co-stars. Coffa’s Gilbert is a sorry caricature of the bushranger. His embarrassing cackling after speaking mere banalities combined with his overbearing facial expressions tip the character most regrettably into Mad Hatter territory. Coffa’s hammy performance renders Gilbert a distracting force in the film. Lee’s Dunn doesn’t necessarily make any significant missteps, but his dainty performance barely makes an imprint on proceedings. Perhaps Holmes himself was aware of this, as he leaves the grisly conclusion for the two characters to the epilogue.

At the same time, Hall’s ex-wife Biddy and his brief lover, Christina McKinnon (Lauren Grimson) are brought to life. Through practised performances, Dobbin is able to emotionally inform us of Hall and Dobbin’s troubled relationship, while McKinnon’s radiance gives Hall good reason to pursue her. Presumably owing to budget constraints, a number of the supporting cast members perform their lines with such a lack of conviction that, at times, the illusion that we are back in 1864 is almost shattered.

Similarly, Holmes could have quite easily limited the number of poor performances by providing us with a more focused first act. Other than featuring Hall, the narrative is scattered, taking us from scene to scene with the introduction of characters who will soon vanish. After the unassured introduction, however, Holmes at least finds a narrative strand and sticks with it: the to and fro journey of robbery that the Hall gang undertakes.

The one thing that is absolutely immune from criticism in the film is the meticulous cinematography. Holmes knows that this is one of his primary weapons of cinematic expression for the film, as many breathtaking shots of the New South Wales plains are interspersed across the film. Even in the more enclosed, intimate spaces, the use of natural light is extraordinary, bringing us back to the rigors of the 19th century. The cinematography in The Legend of Ben Hall is most reminiscent of Alejandro G. Iñárritu’s The Revenant, which really speaks to the visual detail and attentiveness of Holmes and his colleagues.

Although a decent amount of the narrative and characterisation is shapeless and intermittently dull, a sharp third act does its best to cure the film’s main ailments. Sluggish, awkward editing is replaced by quick, engaging cutting that generates momentum as Hall is hunted down. This is aided with the use of lengthy silences and slow motion that rears its head in the inevitable final shootout.

The finale also allows Holmes to manifest his thematic ideas more eruditely. Throughout the film, we are constantly bombarded by instances of Hall’s forgiveness. Hall finally becomes emotionally engaging before it is too late. Similarly, Holmes deftly positions us to question the official narrative that bushrangers were inhumane and the Police guardians of the New South Wales colony, as the police officers in the film dispense with bullets and brutality in equal measure to the Hall gang. And much more than Hall himself.

Holmes’ debut cinematic effort The Legend of Ben Hall initially struggles to assert itself within the realm of the Western genre. Nevertheless, it is able to stumble towards the final act, whereupon the film manages to find some degree of redemption. This Australian film, if for nothing else, is worth seeing for its beautiful visuals and attention to 19th century detail.

The Legend of Ben Hall is in cinemas from 1st December through Pinnacle Films.