There is no doubt that Martin Scorsese is most renowned for his Italian-American crime dramas of the ‘70s and ’80s. It would not be surprising if the layperson was not aware of Scorsese’s strong religious bonds. Famously, Scorsese has encapsulated his life in the following way: “My whole life has been movies and religion. That’s it. Nothing else.”

On a number of occasions, these two things have been mixed together by Scorsese – often to great success. Religiosity in Scorsese’s films has been a persistent theme. There is certainly an undercurrent of religious guilt and morality embedded in films like Raging Bull and Mean Streets.

But Scorsese has also made films that deal centrally with religion. Each has presented different, unique ideas that Scorsese holds about the nature of religious faith. Particularly, Scorsese is immensely interested in one’s own individual relationship to faith.

Scorsese’s first explicitly religious film was the controversial The Last Temptation of Christ. Based off Nikos Kazantzaki’s novel, The Last Temptation of Christ is decidedly a fictional portrayal of Jesus (Willem Dafoe). Scorsese attempts to characterise Jesus as a basically humanly flawed individual, and he, in the process, rids Jesus of his ‘Ubermensch’ properties. Instead of giving us a narrative that idolises Jesus, Scorsese is clearly more interested in Jesus’s relationship to his own humanity, and the humanity of those that surround him.

Jesus’s humanity is primarily fleshed out through his desires and hungers. Subversively, Scorsese canvasses a sex scene between Jesus and Mary Magdalene (Barbara Hershey), conveying that even Jesus was vulnerable to human weakness. Consistent with this, we constantly see that Jesus is not an individual with unflinching self-conviction. If anything, Scorsese goes to great lengths to convey that Jesus lacks this quality. He often questions his faith, and wishes to stray from it. In this respect, Jesus’s imperfect qualities are a product of the weight of being the embodiment of religiosity.

Scorsese’s Kundun is similarly focused on a central, famous religious figure: the 14th Dalai Lama. What is different about Kundun is that it isn’t concerned with Scorsese’s own Christian religion, but with the teaching and followings of Buddhism. By deviating from Christianity, it is clear that Scorsese has the utmost respect for religious observance in a general sense. His engagement with Buddhism is as earnest as his previous Christian undertakings.

In the most basic sense, Scorsese’s Kundun is a recount and brief lesson on the practices of the Buddhist faith. We are informed of the fact that the Dalai Lama is appointed according to the idea of religious reincarnation. The 14th Dalai Lama achieves the greatly important title early in life, and the remainder of the film is an examination of the way in which the Dalai Lama seeks to ‘live up to’ the spiritual role conferred on him.

The Dalai Lama inherits an unenviable political climate, as China is attempting to annex Tibet – the home of Buddhism. While placed under the pressure of imminent Chinese invasion, it is incumbent on the Dalai Lama to preserve the religious order and keep his followers safe. Scorsese portrays the Dalai Lama under considerable strain, and the according way in which he seeks to succeed in pleasing his followers, of which there are many.

Scorsese also conveys to us the unique practices of the Buddhist tradition. In a number of focused close-up shots, we see senior Buddhists sitting at the feet of the young Dalai Lama, in awe of his spiritual symbolism. Typically, we expect that the young idolise the old – but in Kundun we are shown the spiritual strength of Buddhism. None of the Buddhists question its conventions, and this reflects an unending dedication to its ideals, which are tangibly embodied in the idea of the Dalai Lama. In many ways, Scorsese’s Kundun operates as an endorsement of religion and Buddhism.

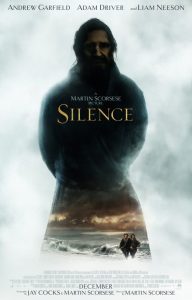

Scorsese’s newest film, Silence, is a return to the religious film. Silence had been stewing in Scorsese’s mind for 30 or so years – and it was finally released 18 years later than Kundun. Unlike The Last Temptation of Christ and Kundun, Silence does not deal with superlative religious figures or icons. Rather, Silence charts the journeys of two Jesuit priests in Buddhist-occupied 17th century Japan. Rodrigues (Andrew Garfield) and Garupe (Adam Driver) are unflinching loyal and faithful to their God and their mentor, Ferreira (Liam Neeson), so much so that they are willing to travel across dangerous Japanese territory in order to spread the teachings of God and rescue Ferreira.

There aren’t too many more dedicated than the two aforementioned priests. They are so convinced of God’s benevolence and meaningfulness that they are willing to sacrifice themselves in God’s name. God is what gives their lives purpose; and the scenes of the film only concern religious subject matter. However, Rodrigues and Garupe both face trying and horrific circumstances: they witness the grisly deaths of their fellow religious adherents at the hands of the Buddhist-dominated police.

Initially, this doesn’t seem to shake their religious devotion. If anything, it makes it stronger. The harm inflicted on the Jesuits only acted to further vindicate their righteousness, and affirm the moral egregiousness of the Buddhists. But there is so much that Rodrigues and Garupe can absorb. The carnage wreaked on the Jesuits pushes them toward inevitable self- doubt. If God did exist, then why did he not protect the Jesuits from such horrible suffering? Is showing disrespect to symbols of God permissible when God is absent in the times in which we need him most?

These questions weigh on Rodrigues in particular. He constantly oscillates between unblinking faithfulness and justified resentment. Matters are only complicated further when we find out that Ferreira, Rodrigues’s mentor, has forsaken God in favour of a life under Buddhist rule in Japan.

In many ways, Silence is an expansion of the ideas of one’s individual relationship to faith. Although we see God questioned by Jesus in The Last Temptation of Christ, it feels as though the crises of belief and hope are portrayed in a more focused, exploratory way. Rodrigues is only a man, whose beliefs in God are brought into question by awful, violent circumstances. And what about the idea of faith itself? Scorsese challenges us to make up our own mind about this, but his own is very clear: that devotion to faith, regardless of the severity of circumstance, is a admirable property of the highest order in our material world.

Silence is in cinemas from 16th February through Transmission Films.