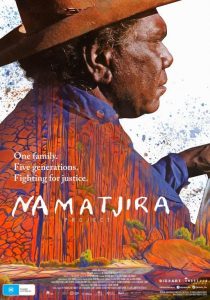

Albert Namatjira was one of Australia’s most talented and accomplished artists of the 20th century. His paintings remain, to this day, an authority on the Australian landscape: of its disarming beauty, its sweeping vastness, its significance to Indigenous Australia. His life, legacy and Indigenous Australian identity are the subject of the Namatjira Project, a documentary by Sera Davies, that eschews straightforward definition.

The Namatjira Project is not simply a biographical retelling of Namatjira’s colourful life and career. Early on, we are given a brief summation of Namatjira’s rise to artistic pre-eminence, focusing on his rich relationship with another Australian painter, Rex Battarbee. We are also sketchily apprised of the racial discrimination to which he was subjected, which makes his lofty achievements all the more remarkable. However, there is a wealth of detail and information about Namatjira missing, such as the fact that he painted over 2,000 paintings over his lifetime.

The documentary also follows the life of a play, eponymously called Namarjira. Born out of a campaign to return the copyright of Namatjira’s works to his family, the play charts and champions Namatajira’s triumphs. Like its subject, Namatjira is a success, travelling around Australia until it eventually finds its way to London. And, as Namatjira did in 1954, the creatives and cast manage to meet the Queen, an event portrayed as unquestionably positive by Davies.

Needless to say, the film does not struggle for content. However, its lack of structure – jumping from focus on Namatjira’s life, to the production of Namatjira, to testimony from his family in Alice Springs – sometimes causes the film to feel shapeless, an ill-defined patchwork. It also means that Davies has to skim over the narrative strands, people and events that crop up in the documentary. Although the benefits are that we get a good overview of Namatjira and his modern-day legacy, it limits the extent to which we can become emotionally invested in the important stories being told. Many of his relatives are given minimal time in front of the camera, usually contributing a thought or two to the documentary. Trevor Jamieson, the actor who plays Namatjira in the play, is interviewed only a couple of times. And when he is, his comments are usually directed at praising director Scott Rankin, or Namatjira himself. However, it is doubtless that Jamieson is a worthy subject of examination, and we cannot help but wish that Davies spent more time pondering his thoughts, experiences and perspectives on contemporary Aboriginality and race relations.

Davies is clearly a competent documentarian, evinced by her ability to balance various strands of what is a holistic story of the merits of, and hardships faced by, Indigenous Australia. The campaign around which she chose to frame this documentary – to grant the Namatjira family the copyright over their relative’s art – is an important, appropriate symbol of the Indigenous experience since the late 18th century, one defined by dispossession and unspeakable neglect. Her experience in documentary film has primarily been with NGO and the ABC, which shows in the Namatjira Project; as the film can feel more like advocacy and reportage than an unbridled, impassioned cinematic endeavour.

The one person that is fully fleshed out by Davies is Namatjira’s grandson, Kevin. He is invariably shy but quietly assertive to the documentarians, and even to Prince Phillip in the latter stages of the documentary. He tells the camera, that when he meets the Queen he will ask her “to help us get some land.” Like his grandfather, Kevin is a painter, but he endures through life without a home, car or job. But he is, undoubtedly, still whole without those commodities, conscious of his unbreakable connection to the land of Alice Springs.

The most substantial shortcoming of the Namatjira Project is the brevity over which details are skimmed, the superficiality with which stories are sometimes told and recounted. This documentary was certainly made for the right reasons, and it is worth seeing if only to galvanise us to reflect on our past and to correct our future.

The Namatjira Project is in cinemas from 7th September through Umbrella Entertainment.