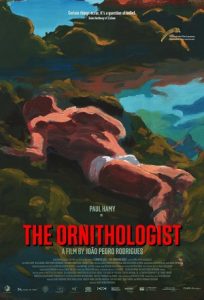

If you had John Waters remake Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1979 Stalker the result might end up resembling The Ornithologist, the latest feature from Portuguese arthouse director João Pedro Rodrigues. This is a challenging, enjoyable and vastly weird movie. It’s many more things than that and almost certain to illicit varied reactions from most boring film of the year to best film of the year.

The film is a re-imagining of St Anthony of Lisbon’s life. No need to Wikipedia him before going into the film; just know he is the patron saint of lost things. If you like your movies linear with mono interpretations and familiar story arcs this isn’t the film you’re looking for. If you enjoy passionate discussion on what the hell x scene meant, and enjoy the surrealistic dream like qualities of Lynch and Bunuel, this is a must see.

The beginning of the film follows ornithologist Fernando (Paul Hamy) navigating Portuguese forest mostly by kayak. He is looking for rare storks when he capsizes and becomes unconscious in dangerous waters. Later Fernando is resuscitated by a pair of Chinese missionaries. The trio get along nicely until a campfire talk, when the girls reveal to him that they are cursed and he must help them escape the forest. Atheist Fernando dismisses their supernatural concerns and tells them he will be going a separate direction and that they should all sleep on it. In the morning he awakens bound by ropes suspended above the water, now their prisoner.

The capsizing event in the movie mirrors the life of St Anthony, born Fernando. In the early 13th century as he sailed home to Portugal a gale blew his ship of course and he landed in Sicily. From there the circumstances of his life led him to becoming an ascetic hermit, living in a small cave as a monk.

After escaping the ropes in the dead of night Fernando steals away with a few of his possessions, only realizing the next day the girls still have his map. From here the film becomes by slow degrees a story of survival, and the strong theme of man vs nature emerges continually as Fernando trudges through the forest. Mirroring the survival tale are increasingly less lucid encounters Fernando has with fellow people, animals and objects within the forest. These encounters are thrilling, sometimes sexual or bizarre, and all highly allegorical with biblical overtones.

When Fernando is out of sync with the forest the score mirrors that sense of foreboding overcoming the background nature melody with a disjointed chorus of jarring strings. There is a wonderful poetry within the film’s essence. Rodrigues is happy to let the camera idle passively when needed, allowing for the contemplation needed for this deeply existential journey. This is a near perfect execution of cinematic vision with a harmony of ambiguity and clarity that is rarely achieved.

The Orthinologist is in cinemas from 2nd November through Sharmill Films.