It should come as no surprise that Ferenc Török’s 1945 takes place in 1945, at a time of great tumult for Hungary. The Nazi regime had been banished mere months before, and the Soviets were about to occupy the homeland. In the coming years, Hungary would become a socialist state, and remain that way until 1989. What is perhaps more unexpected is the relatively unknown sequence of these events, the way in which they have shaped the culture and consciousness of Hungary. At this level, Török’s film is educative, providing us with a historical sketch of mid-20th century Hungarian life.

However, this isn’t to say 1945 is documentary-like in its observance of Hungarian politics and society. Török’s approach is significantly different: shifting between still and silent imagery, and the tiredness of melodrama. Szentes István (Péter Rudolf) is a councilman in a remote village who’s done quite well for himself. He presides over the village’s operations, and owns several houses and businesses, one of which he has handed over to his son, Árpád (Bence Tasnádi). The film is framed around an important day for the Szentes’, as Árpád is set to marry his fiancé, Kisrózsi (Dóra Sztarenki). The day, however, isn’t without problems and complications: István is incensed with his wife, Anna (Eszter Nagy-Kálózy), on account of her drug habits; Kisrózsi’s rugged ex-flame Jancsi (Tamás Szabó Kimmel), has returned to the village, harbouring questionable motives; and Hermann Sámuel (Iván Angelus) and his son (Marcell Nagy) travel on foot steadily and inexorably towards István’s council building. Exiled by the Nazis for their Jewish identity, the Sámuels surge back to reclaim their home and property, which has been appropriated by István’s council. Out of all the issues confronting István, this is the largest – and indeed, forms the moral crux of the entire film.

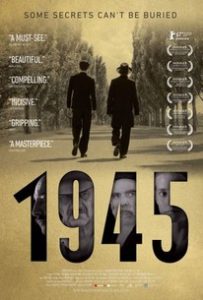

Török’s crisp black-and white photography is what first strikes you about 1945, but it’s not long before you start noticing some of its critical defects. The characters almost perfectly fit stereotypical moulds: the domineering and abusive husband, the sullen and withdrawn wife, the cowering son, the indecisive fiancée. There’s occasionally a necessity for filmmakers to be in touching distance with stereotype and archetype, for it makes their characters digestible and identifiable. Török has gone much too far here, and it shows: most of the early scenes run only on the fuel of melodramatic tensions, evasions and conflicts. The film’s saving grace lies in its second narrative strand, the one following the Sámuels’ strange, indomitable journey to the village.

Perhaps the issue with the story is that Török is too explicit; rather than gesturing or edging us towards some kind of clarity, we can tell what he’s going for a mile off. This is especially true for the wedding plot contrivance – Kisrózsi and Árpád couldn’t be married in peace, now could they? Quite interestingly, then, the Sámuels’ mostly silent, slow-moving trek – which, at times, feels biblical – remains ambiguous and unexplained until the film’s coda. The images are rather left to signify for themselves. And, they are some of the most striking of 1945: possessed by a white aura, of a simplicity and austerity that recalls Pasolini’s The Gospel According to St. Matthew. This dissonance is not jarring so much as illuminating.

In all, the film’s weighty ideas, of guilt and shame, avarice and ruthlessness, dispossession and usurpation, are still able to come to the fore. It’s in the expression of these ideas that 1945 finds solid footing and its purpose as a cinematic work. Who’s worse, the Nazis that expelled scores of Jewish men and women from Hungary, or the denizens who unrepentantly benefited from the Nazis’ actions? Questions like these keep us referring back to 1945 long after its last black and white frame is projected onto the screen, questions that both engage with history and broader matters of morality and ethics.

At 91 minutes, Török’s film tends to feel longer than it actually is. Whether this is because of the spectrum of ideas it explores, or the elongated, lagging nature of some of its scenes, is up for debate. Though, it’s clear 1945 is a deeply uneven film. One gets the impression this outcome could’ve been averted with better drafting and more fine-tuning from Török. But it’s something that we, like István and his cronies, will have to live with.

1945 is in cinemas from 29th March through JIFF Distribution.