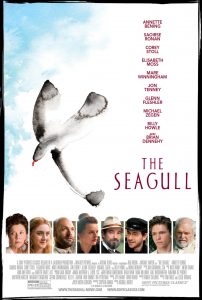

Russian literary master Anton Chekhov’s The Seagull has undergone many transformations on both stage and screen since its debut in St Petersburg in 1896, but until now has not had a faithful, period, English translation set to film. Considered one of the literary great’s best comedies, Michael Mayer’s most recent homage is a lovingly absurd re-staging, replete with melodramatic performances and simply oozing with subtext. It is somewhat surprising, upon enjoying a screening, and learning of ballet, opera, musical, screen and theatre adaptations in England, America, Canada and even Australia, that The Seagull in its period form has not previously been adapted for the screen in English. And what a treat audiences are in for now that it has.

Saoirse Ronan and Billy Howle are thrown together again (after last year’s On Chesil Beach), seemingly typecast, as young couple Nina and Konstantin, whose foibles are exacerbated by a lack of communication and hotheaded schemes and desires, again. Living in the countryside a horse and carriage ride from Moscow, Konstantin’s mother, the fading actress Irina (played marvellously insufferable and deliciously delusional by a brilliant Annette Bening) is home for the summer with her younger lover, the famous writer Boris (a familiarly smug yet alluring Corey Stoll). While staging his own play starring his love Nina, Konstantin is chided by his mother, seemingly incapable of not being the centre of attention at all times, and thus begins a rather dramatic meltdown consuming all around.

The film’s structure is melancholy and quiet, there are no great dramatic moments, the story progression relies entirely on conversation, subtext and the expertly cast supporting players, lead by an ever brilliant Elisabeth Moss as Masha, the house manager’s daughter who is mourning her life and drowning her sorrows in vodka and quick asides, and the occasional outburst at the besotted school teacher Mikhail (Michael Zegen) who worships her. Moss proves once and for all that there are no small roles, only small actors, stealing every scene with just a look, and delivering a deliciously melodramatic portrayal of unrequited love.

Annette Bening is far and away most valuable, reeking of vanity and jealousy at the young ingénue Nina, even going so far as to push her son and tell him he’s “nothing” mere days after a suicide attempt, rather than lose an argument to him. The tension and humour are palpable and the material has aged remarkable well given its Russian symbolist origins. Every situation, though entirely driven simply by conversation, is ripe with comedy and drama. While some lines are delivered with the insufferable sincerity of the theatre and seem utterly absurd on the screen – the inescapable “play within a play” trope pops up in Act I, and the extended, overly dramatic monologues about literature, fame and love do drag from time to time – the slavish devotion to the original material has not made this adaptation any less enjoyable.

The Seagull is in cinemas from 4th October through Transmission Films.