The media loves to tell tales about young people causing trouble and is quick to categorise groups of youths as gangs or to assume the ill-intentions behind a young person’s unsavoury behaviour. Seldom do we ever hear from these young people themselves and perhaps there’s part of us – as a society – that isn’t really willing to listen anyway.

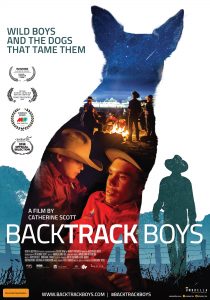

With this in mind, Backtrack Boys is a much-needed contribution to the Australian discourse. This homemade documentary, directed by Catherine Scott, is a rare film that gives troubled youths a platform to speak and reclaim their self-worth. It doesn’t necessarily paint them as heroes, nor does it try to justify their behavioural issues. Rather, it focuses on the strengths of each individual featured and their capacity to reinvent themselves for the better.

The film primarily follows three boys who participate in Backtrack, a youth program based in Armidale, NSW. The program offers youths who have had trouble with the law an alternative path to rehabilitation, one vastly different to the juvenile incarceration systems set up by Australia’s legal system. Initially the film focuses on Paws Up, the program’s dog-jumping component that sees the boys paired with dog companions. In these early scenes, we’re able to see some obvious benefits to the program – one that gives teenagers something to take responsibility for, as well as giving them a chance to showcase their softer side.

As the documentary progresses, we learn that this isn’t purely a feel-good narrative where every participant in the program experiences a positive linear progression from juvenile delinquent to upstanding civilian, and nor should it. There are times when all three of the main boys featured – Zac, Rusty and Tyson – are in trouble with the law and we are left to watch as these boys must respond to these incidents in real time. As you watch these events play out, it really dawns on you that this is reality and that the very characters you have grown to empathise with over the course of the film might not get their happy endings.

Each of Zac, Rusty and Tyson – among other boys in the program – are given the chance to share their life stories and their rationalisations on camera, and this is where the film is at its best. As we directly hear their voices, we learn that these boys have, in many ways, drawn the short straw in life. For some of these kids, it’s behavioural disorders; for others, it’s family violence issues or the loss of a parent.

If there is a hero to this film, it’s Bernie Shakeshaft, not that he’s the type to accept much praise. As the Backtrack manager, Bernie is the father figure and mentor that so many of these boys need. The way he interacts with the participants and the amount of effort he puts in is inspiring and will no doubt make him a role model to anyone who watches the film.

It’s almost impossible not to be moved by Backtrack Boys and feel emotionally connected to the teens you meet on screen. But Scott doesn’t want you to leave with just tears in your ears or anger in your hearts; she also challenges you to think deeply about your attitudes towards rehabilitation. For the boys in the Backtrack program, it’s clear that incarceration is not the answer to their problems; for the audience, they too must consider what a better juvenile justice system in Australia might look like, not to mention how our media can communicate a less harmful narrative.

Backtrack Boys is in cinemas from 25th October through Umbrella Films.