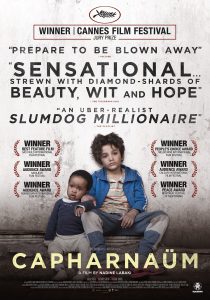

Is it fair that our children often bear the burden of the worlds that they are brought into? Capharnaüm, directed by Lebanese director Nadine Labaki, confronts this question by focusing – with brute emotional force – on the impoverished life of a child on the wretched streets of Beirut. The screenplay, written by Labaki and her collaborators Jihad Hojaily, Michelle Keserwany, Georges Khabbaz, and Khaled Mouzanar, is uncompromising and unrelenting in its social realism. At times, its portrayal of poverty may seem to veer into the didactic. But through Labaki’s visceral direction and an astounding central performance, the film largely manages to steer clear of condescension. It is harrowing and it is heartbreaking, but the film nevertheless implores us to see and find the humanity in the inhumane.

Undocumented twelve-year-old Zain (Zain Al Rafeea) is suing his parents – his mother Souad (Kawthar Al Haddad) and his father Selim (Fadi Kamel Youssef) – in court. The crime is, in his words: “Giving me life!” The film then goes back in time and traces the events which led to this searing accusation. At the beginning of the film, Zain is living with his parents and several siblings in a crowded, decrepit apartment in Beirut. After his adolescent sister Sahar (Cedra Izam) is sent off by their parents to an arranged marriage, Zain runs away from home. Equipped only with resolute resourcefulness and an emotional maturity beyond his years, Zain scrapes together whatever he can find to eke out a meagre living among refugees in an informal settlement. Eventually, he meets Rahil (Yordanos Shiferaw), an Ethiopian refugee working as a cleaner, and in exchange for staying with her he babysits her child, Yonas (Boluwatife Treasure Bankole), while she works. Soon, the situation becomes increasingly dire, desperate, demoralizing and, in the end, devastating.

What anchors the film is Labaki’s unwavering direction. Grounded, raw and empathetic, Labaki infuses every scene with a commitment to honesty. Her realistic portrayal of abject poverty and hopelessness is, simply put, overwhelming. And vital to this portrayal is Al Rafeea’s moving central performance. As the perceptive, practical Zain, he is remarkable, and how Labaki managed to conjure a performance of this stature is a small miracle. But saying this, perhaps, would unfairly detract from Al Rafeea himself. He navigates the film’s heavy subject matter with rich and instinctive emotional openness, so much so that he manages to find fleeting glimmers of warmth, and even humour, amidst the misery and bleakness.

To some, the film’s initial premise, in which Zain is suing his parents in court for giving birth to him, may seem contrived – an unsubtle means to lead to preaching. And, to some, the film as a whole may seem garishly indulgent – unsubtly insistent in its demands for pity. But this would be unfairly cynical. The inability for most of the audience to directly relate to the subject matter arguably means that confronting it head on is the only way to give the reality – of its subject and for its subjects – justice. It is only by refusing to look away that necessary truths can be conveyed, and it is this refusal that lends the film its palpable, undeniable power.

Capharnaüm is in cinemas from 7th February through Madman Films.