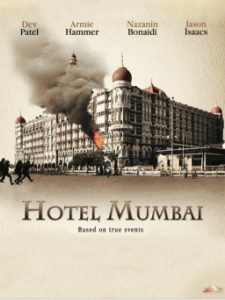

In November 2008 ten members of a terrorist sect operating out of Pakistan traveled to Mumbai. Over four days they massacred 174 people. In one of the most heinous acts of 21st century terror this tiny but organised group ended the lives of several hundred and brought India and Pakistan to the brink of war. Hotel Mumbai, the debut feature of Australian director Anthony Maras, brings these terrible days to the screen in one of Australia’s all time best first films. And don’t let the presence of Dev Patel working at a hotel in India lead you astray; this is emphatically not a Best Exotic Marigold Hotel sequel). Scarier than any recent horror film and with a gaze that never wavers, this is the kind of experience that will chill audiences to the bone.

Based on Victoria Midwinter Pitt’s 2009 documentary Surviving Mumbai, Maras and his large cast take us from the beginning of the attacks to the siege of the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel, where hostages were taken and later executed. Much of the time is spent with Arjun (Dev Patel), a waiter working in one of the hotel’s five star restaurants who, alongside many of the staff, risks his life to protect the guests. He was just one of the many unfortunate souls who happened to be there that day, alongside Armie Hammer and Nazanin Boniadi as a wealthy international couple who were visiting with their Australian nanny (Tilda Cobham-Hervey) and six month old daughter. Jason Isaacs as a shady Russian plutocrat and Australian backpacker Natasha Liu Bordizzo are just some of the many who were held up during those fateful days, as they all ask and answer questions about themselves that no one should ever have to find out.

After making three award winning short films, Maras has crafted the year’s most unsettling film. Never averting his gaze from the horrific violence that surrounded these people and making sure every drop of tension is rung out of each moment, this homegrown white-knuckle thriller (it was largely filmed in Adelaide) is one of the finest made about modern terrorism.

Importantly Maras hasn’t sold out to the fear mongering paranoia that has plagued so many like-minded films. This is both a moving tribute to the Indian people – most of those killed in the siege were staff members who chose to stay and protect their guests – and a scathing indictment of the fanatics that committed these terrible crimes. Yet it wisely decides to go deeper. Many other directors wouldn’t have approached it from this angle, but as an audience we are forced to wrestle the unwelcome but important fact that men like this don’t operate in a vacuum. The screenplay by Maras and John Collee does a fine job of prosecuting not only the men who committed these heinous crimes, but the world at large for creating their blueprint.

Living in the abject poverty of India and Pakistan while watching rich foreigners live like royalty would make anyone angry with their lot in life, especially when people come to their homes with no understanding or respect for millennia old traditions – like Armie Hammer ordering a cheese burger with beef in the middle of India. Appalling pollution corrupts the water they drink and the very air they breathe. The shadow of luxury hotels falls on the open sewered slums outside their walls.

As they approach the city, with the leader of their fundamentalist group speaking to them through their phone’s ear pieces – literally like having the devil on their shoulder whispering instructions – they see the financial capital of India for the first time. “Look at what they took from you” he says. A lot of this dialogue isn’t invented; most of it was taken from the transcripts of the intercepted phone calls during the siege. Upon entering one of the upper class rooms two of them are dumbfounded with the toilet, having never seen one with running water before.

Couple this with the fact that most of the perpetrators were men in their early twenties. As one of the policemen comments upon seeing them on CCTV: “They’re just boys.” Some of them hadn’t started shaving yet. In lands where education is a privilege denied to millions and religion is a factor in everyday life it’s no wonder that young men, barely out of adolescence and lured with the promise of earning their families money, become radicalised. As the voice in their ear assures them what they’re doing is necessary and just, they truly believe they’re the heroes of this film.

The film’s style seems to ape the films of Paul Greengrass. A sense of ultra realism where human failings are front and centre, extreme times bring out both the best and worst of those involved. It’s a style that can slip philosophy in too, as the few well-aimed jabs at religion land squarely. The walking hypocrisy of a self proclaimed religion of peace calling its sons to massacre innocent people should never be overlooked. So too are strange ways that religious morals can crash up against each other – upon machine gunning a young woman one of the attackers refuses to reach under her shirt to look for a passport… because that would be a sin. This is best summed up by Jason Isaacs’ character who, deciding to to make a run for it, is told “You have my prayers” by one of the hotel staff. “Prayers are what started this” he replies.

Hotel Mumbai is the first cinematic gut punch of the year. It’s not an easy watch but the kind of difficult yet important experience to which our gaze should not be averted. Human evil does not spring fully formed out of a void, and it’s films like this give us the tools to begin to understand and combat these terrible forces. It’s a stunning debut that that will leave audiences everywhere flocking to the nearest bar for a stiff drink and a quiet cry when it’s over.

Hotel Mumbai is in cinemas from 14th March through Icon Film Distribution.