Lazzaro (Adriano Tardiolo) shouldn’t be as content as he is. He is exploited by just about everyone he knows — all the way from the marquise on whose tobacco farm he works, to his extended family of share-croppers who continue to serve her in spite of their non-existent reward.

She exploits them, they exploit Lazzaro — innocent, faithful and mild-mannered peasant that he is. In one wistful scene, the only word we hear as Lazzaro works the crops is his name called out over and over, beckoning him and him alone, back and forth, before falling to a whisper as the children of the farm tease him. To this family he may as well be a donkey. Helpful, loyal, docile.

But he never complains, perhaps because he never questions. Even though he is, to all intents and purposes, a slave and doesn’t even merit a place to sleep in the house, he takes pride in being a hard worker and in serving the only reality he knows.

All this changes when Lazzaro meets Tancredi (Luca Chikovani), the marquise’s son, who despises his parents’ legacy and harbours a feverish imagination. Sensing an opportunity in Lazzaro, he concocts a false kidnapping plot in a wild bid to escape. In drawing attention to his mother’s practices he triggers irrevocable change to the lives of all.

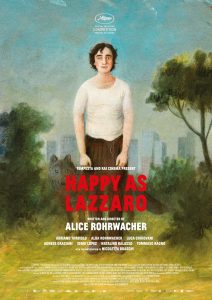

Writer-director Alice Rohrwacher‘s Happy as Lazzaro is a patient film, set up by the mesmerising cinematography of Hélène Louvart, who manages to find beauty in the hard toil of this commune. In this isolated enclave’s quietude there is something otherworldly, as if these poverty-stricken farmers were not simply rooted in a feudal agricultural tradition but displaced in time. Perhaps they are. They don’t seem discontent, but neither do they seem happy. They simply exist within a structure they have not chosen but have resigned themselves to.

This is an overarching theme, and for a film of so dramatically different halves and so narratively abstract, it is surprisingly effective. At the film’s midpoint, from a sun-drenched tobacco farm Rohrwacher’s Italy is wrenched forward decades and into the present, where the city manifests grey and oppressive. The slaves have been freed, only to be set upon by a new breed of metaphorical wolf, forced to flog stolen goods for scraps amid a tangle railway lines. In so doing the current social climate is viewed in the context of all the lessons that might have been learnt if history hadn’t been forgotten.

When Antonia (first played by Agnese Graziani, later Alba Rohrwacher), arguably the only person apart from an erratic Tancredi to ever pay much genuine concern for Lazzaro as a person, narrates a mythical story of a saint and a wolf in the wilderness, we understand the frame in which Rohrwacher wants us to empathise with these folk. This is less a film about these particular people than an allegory for the fate of her home country. Rohrwacher is scathing. Mild magical realism around the journey of Lazzaro, too innocent to be true, portrays the shortcomings of his world as religious fable, and the plight of this small community, stagnant and isolated from a developing world, soon becomes analagous to a wider section of the the Italian population.

Playing on themes of innocence, exploitation and predation, Happy as Lazzaro at times makes for a hopeful portrait that is often amusing and heartwarming in its characters’ pursuit of something good in spite of their stature. Its commentary on forgotten history, entrenched neglect of the poor and cyclic abuses of power can’t help but paint a grim picture, but thankfully in Rohrwacher’s hands it is a picture well worth the illustration.

Happy as Lazzaro is in cinemas from 6th June through Palace Films.