Last year the United Kingdom was forced into quite an embarrassing retreat over its treatment of some members of the Windrush generation, so named after the HMV Empire Windrush, which landed in Britain in 1948 from the Caribbean. This was just the start of a tide of immigrants invited from commonwealth Caribbean countries in the wake of World War II to fill a dire labour shortage in the motherland. As recently as a few years ago it had been revealed that members of that generation who had arrived as children under their parents’ passports were under threat of being deported for not being able to demonstrate citizenship, despite many having lived in the UK for upwards of 50 years. Since then a government apology has been issued, but such a moment of uncertainty deserves more scrutiny.

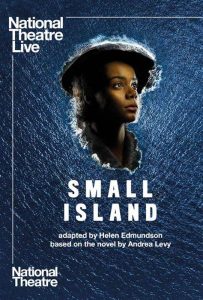

A play such as Small Island, the Helen Edmundson’s stage adaptation of Andrea Levy’s celebrated novel of the same name, is one step towards addressing what might have become a collective amnesia of how the commonwealth’s colonies have contributed to making the England of today. It takes a snapshot of a country in crisis, the people who bore them through it and, in admitting failures of the past, affirms support for migrant communities who arrived expecting opportunity only to be greeted with injustice and ingratitude. Sadly this production comes just a little too late for Levy, who died in February this year. It is doubly sad given how impressive this staging by Rufus Norris is.

Ranging from life in Jamaica during the war to the year of the Windrush’s docking, Small Island follows a handful of lives: Hortense (Leah Harvey), who longs to venture beyond rural Jamaica and teach; her childhood friend Michael (CJ Beckford), who is enlisted for military service; Gilbert (Gershwyn Eustache Jnr), a jovial Jamaican on his way to England to become a lawyer if given the chance; and Queenie (Aisling Loftus), the daughter of a Lincolnshire pig farmer who in the absence of her conservative husband opens up her house to a succession of servicemen and migrants.

This title could be taken to allude to a number of things. In Small Island Jamaica is a small island whose modest size struggles to contain bigger dreams. The expression ‘small world’ also comes to mind when describing England with the way these characters gravitate to each other in spite of the larger events surrounding them. But a small island also means living in close proximity, and it is in London’s densely inhabited domestic environment that the tensions – cultural, racist, classist and gendered – of Small Island are most taut.

This title could be taken to allude to a number of things. In Small Island Jamaica is a small island whose modest size struggles to contain bigger dreams. The expression ‘small world’ also comes to mind when describing England with the way these characters gravitate to each other in spite of the larger events surrounding them. But a small island also means living in close proximity, and it is in London’s densely inhabited domestic environment that the tensions – cultural, racist, classist and gendered – of Small Island are most taut.

Most people would have made sacrifices during the war, and so thwarted dreams is an inescapable theme. But it is especially true of the Caribbean community here. In Small Island Jamaican servicemen are misled in signing up to the army, promised equality only to be greeted with suspicion and derision. A teacher’s qualifications obtained in Jamaica, a commonwealth colony, aren’t deemed suitable for a teaching job in England. A community who served the empire and were promised an equal place living and working in British society are treated like second-class citizens. And a woman such as Queenie, daring to defy the tides of racism dividing post-war society, is met with trial by association. No-one it seems is immune to such regressive attitudes.

This play may respond to a particular time in history, but it also confronts lasting truths in its depictions of blind discrimination eroding the fabric of a society. Australia is no stranger to this phenomenon. We had our own post-war influxes of migrants in multiple waves, and we need only watch the 6pm news to see that barriers to integration and the ‘fear of the other’ that Small Island explores have never gone away, which makes this play immediately relevant to our own discussions of cultural acceptance. And it does so with some vigour. Levy’s narrative is instructive, acting as a microcosm of a nation’s attitudes and ambitions, and no less impressive is Norris’s dexterity in being able to capture the chaos, the poverty, the cruelty but also – importantly – the humour of such complex material through a combination of stage design, lighting, projection, deft deployment of up to 40 actors and an infectious Caribbean jazz soundtrack. Biggest plaudits, however, might best go to the leading trio of Harvey, Eustache and Loftus, who ensure that, at a formidable 3 hours and 10 minutes, not a second is wasted.

NT Live: Small Island will be playing in selected Australian cinemas from 3 August through Sharmill Films.