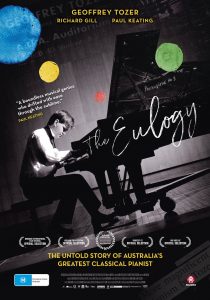

At the age of 54, destitute and alone, Geoffrey Tozer died in his rented Melbourne home. In a stinging 45-minute obituary Paul Keating, a long-term fan, described it as a national tragedy. “For the Australian arts and Australian music, losing Tozer is like Canada having lost Glenn Gould, or France, Ginette Neveu. It is a massive cultural loss. The kind of loss people felt when Germany lost Dresden”. “[Members of the Australian art establishment] should hang their heads in shame at their neglect of him.”

Tozer’s skill with the piano dwarfed almost all his contemporaries. Widely toted as a child prodigy and later a genius, he composed his first piece aged seven. He could transcribe what he heard instantly, improvise in the style of any one of the great composers on request, and was able to transpose an orchestra score to a piano score simply by looking at the sheet music. Rhys Boak, one of his contemporaries, declared him “the finest pianist of the 20th century”. The man was a homegrown, once in a generation talent, the toast of some of the finest orchestras in the world – so how can it be that no one seems to have heard of him?

Janine Hosking, working alongside the late conductor and musical educator Richard Gill (many will know him as a beloved recurring guest on Spicks and Specks) and supported by the MIFF premiere fund, set out to find the story of Tozer. What went so horribly wrong with the Australian arts establishment that an artist like this slipped through their fingers?

In his titular eulogy Keating took no quarter with his targets. “If anyone needs a case example of the bitchiness and preference within the Australian arts, here you have it”. At first glimpse it seems that Tall Poppy Syndrome played a large role in Tozer’s downfall. As we go deeper into this story that turns out not to be the only explanation, but this uniquely Australian curse was a factor. It has always been one of Australia’s major quirks. We take ourselves seriously enough to be passionate, yet when an individual gets too far ahead of the pack the sad legacy of our cultural cringe seems to cause a knee-jerk reaction against them. It’s in all aspects of our culture, from politics to the economy. It’s one of the sad legacies of our past that helped bring down an artist whose name should be up there with David Helfgott or Dame Nellie Melba.

In his titular eulogy Keating took no quarter with his targets. “If anyone needs a case example of the bitchiness and preference within the Australian arts, here you have it”. At first glimpse it seems that Tall Poppy Syndrome played a large role in Tozer’s downfall. As we go deeper into this story that turns out not to be the only explanation, but this uniquely Australian curse was a factor. It has always been one of Australia’s major quirks. We take ourselves seriously enough to be passionate, yet when an individual gets too far ahead of the pack the sad legacy of our cultural cringe seems to cause a knee-jerk reaction against them. It’s in all aspects of our culture, from politics to the economy. It’s one of the sad legacies of our past that helped bring down an artist whose name should be up there with David Helfgott or Dame Nellie Melba.

Richard Gill, who tragically died of cancer last year, is an excellent presenter. He’s a lovable personality guiding us through this journey without taking the focus on Tozer himself. The man lived his life to spread his passion for music and if this is the final film he was involved in it’s a wonderful goodbye.

If there’s one thing that holds The Eulogy back it’s the rather tame nature of it all. It’s clear that everyone went into the making of this film thinking they’d uncover long lost secrets or kick in the door of the elitist world of Australian classical music. There’s nothing that surprising. It lacks that extra discovery that all great documentaries have. It’s no one’s fault of course – none could have predicted what Gill and Hosking would or wouldn’t find – but apart from getting to know Geoffrey Tozer’s musical talents there are few moments that leap off the screen or fascinating interview subjects.

Anyone who loves classical music, particularly the local scene, will love The Eulogy. Australia’s artistic world is always worth exploring and someone as talented as Geoffrey Tozer deserves to be added to its canon. He was denied it in life, let’s give it to him in his death. As Keating finished:

“When one has been touched by the stellar power and ethereal playing of a sublime musician, one is lifted, if only briefly, to a place beyond the realm of the temporal. Geoffrey Tozer did this for many people. His remembrance is the small recompense we give him in return.”

The Eulogy is in cinemas from 10th October through Madman Films.

This film became increasingly tedious to sit through after about twenty minutes. Congratulations on wasting my time Janet hosking or whatever your name is..I would rather have watched paint dry. I can’t think of anyone more in need of film school.