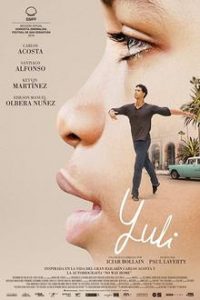

For those unfamiliar with the world of ballet, the immediate significance of Icíar Bollaín’s Yuli, a biopic detailing the rise of Cuban dancer Carlos Acosta, may need some explaining. Acosta, known mostly as Yuli, was a restless boy growing up in Castro’s Communist regime in the 70s and 80s. He idolised Michael Jackson, break-danced on the streets, flunked school and harboured far-fetched dreams of playing soccer for a living, all the while consigned to an upbringing of poverty and harsh lessons. And yet from these humble beginnings he would somehow become one of the world’s most famed ballet dancers and the first black ballet dancer to dance many of ballet’s most iconic roles.

It’s a story that proves to be a fascinating and infectious one, even if such maturation was, as told here, not without its setbacks. At times the struggle for someone so gifted appears not to have been the dancing itself but a life on the road that deprived him of a connection with home while Cuba, his family and friends included, endured such immense hardships—hardships that natural ability seemed to exempt him from. While Acosta had moved to the UK, he continued to call home and ask after his family, even admitting to hate the profession he was initially pushed into by his father Pedro (Santiago Alfonso). But each time he is rebuffed by Pedro with the same message: forget about family, homesickness will get you nowhere.

This relationship is one of a few reasons Yuli comes across as a peculiar film. It is largely a dramatised retelling, but nonetheless Acosta himself is heavily involved. He appears in the modern day with his dance troop Acosta Danza, acting as narrator and even going so far as to orchestrate some choice snapshots of his life through a series of autobiographical dance performances. Otherwise in the film he is played first by Edison Manuel Olvera as a young boy struggling to live up to his father’s expectations while also maintaining a normal life, and then Keyvin Martínez as a young man struggling to adapt to his new life and its globetrotting trajectory, forever being pulled away from Havana, sometimes against his will. Both actors hold themselves well and sustain an energetic, physical and often moving portrait of this singular artist.

Such a gamble of mixing reality with re-enactment could have been disastrous, but in all Yuli is an ambitious and resounding achievement. Some of this is down to Acosta’s energy and grace, bringing a refreshing Cuban flavour to what can be a rather austere artform. But his direct involvement can be assessed in further lights. His dance troop’s performances provide a novel storytelling experience that demonstrates Acosta’s creative versatility while offering a heartfelt look into his mental state during certain pivotal moments in his life. At their core is his relationship with Pedro, and while Acosta’s father can appear brutal, violent and fierce at times, he is ultimately seen in positive and loving terms. Such a viewpoint can only have come from Yuli, as an impartial observer may not have looked on Pedro’s legacy of parenthood quite so forgivingly.

Such a gamble of mixing reality with re-enactment could have been disastrous, but in all Yuli is an ambitious and resounding achievement. Some of this is down to Acosta’s energy and grace, bringing a refreshing Cuban flavour to what can be a rather austere artform. But his direct involvement can be assessed in further lights. His dance troop’s performances provide a novel storytelling experience that demonstrates Acosta’s creative versatility while offering a heartfelt look into his mental state during certain pivotal moments in his life. At their core is his relationship with Pedro, and while Acosta’s father can appear brutal, violent and fierce at times, he is ultimately seen in positive and loving terms. Such a viewpoint can only have come from Yuli, as an impartial observer may not have looked on Pedro’s legacy of parenthood quite so forgivingly.

And having admitted the gamble in bringing Acosta in on his own story, such an approach does beg the question of what a film not so directly influenced by Acosta might have looked like. Occasionally the story at home in Havana appears more compelling, and admittedly more in need of telling than his own, hence his willingness to get back there. Indeed we see glimpses of Cuba’s plight, hear perilous plans of Acosta’s friends to build boats to escape to America, and we see the grief of his mother at her family leaving her behind as they move to Miami. His sister Berta’s story is even more tragic, and deserved perhaps more time than is allowed here. Although that said, Yuli still strikes a nice balance between Acosta’s achievements and the cloistered frustrations and mental toll of Castro’s Cuba.

With Acosta having drawn comparisons to Rudolph Nureyev during his career, it seems fitting that we might contrast Yuli with Ralph Fiennes’s recently released The White Crow. In both contexts ballet acts as an escape portal from overbearing political regimes, but that is about where the similarities end. This is a much sunnier affair, Havana being a long way from Siberia in character and climate, and it is the better for it.

Yuli is in cinemas from 31st October through Limelight Distribution.