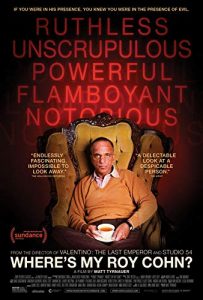

He may not be a household name, but Roy Cohn may well be one of the chief corrupting influences of American leadership since the 1950s. A brash, conniving, tactless but brilliant (in his way) lawyer, he is even described early in Matt Tyrnauer‘s documentary Where’s My Roy Cohn? as ‘pure evil’. To subject yourself to a 97-minute catalogue of Cohn’s dubious achievements and personal contradictions may seem a tad masochistic. But horror and fascination often go hand in hand, and Roy Cohn, for all his faults, is a fascinating character.

For Tyrnauer’s purposes, Cohn’s public life divides neatly into three parts. The first two of those sit either side of the 1954 senate army hearings into allegations relating to abuse of powers. Cohn had tried to wrangle a plush Pentagon post for a close friend, David Schine, to avoid him being sent to the front line, and was being grilled for it. By that time Cohn was a sharp and ambitious legal aide to Senator Joseph McCarthy. Despite only being in his mid-20s he had made a name for himself in Washington for successfully prosecuting a death penalty for Julius and Ethel Rosenberg on charges of spying for Russia and also helping McCarthy to hunt down and expel homosexuals and communists from government employment.

Original footage from the army hearings is particularly compelling as Cohn is forced to squirm before a cringeworthy barrage of homophobic derision as his ‘warm’ relationship with Schine is laid bare. He would deny his own homosexuality forever after, even in his dying days, but in that moment of humiliation his promising career took a turn. Far from a shrinking violet, he would utilise that anger to become one of the most notorious legal and political forces in America.

Much psychoanalysis is employed in tracing the origins of this man’s apathetic yet magnetic personality, and the list of interviewees willing to deal out the goss is both impressive and telling. Legal associates, gossip columnists and even cousins are all eager to recount stories damning, amusing and intimate about everything from Reagan to face lifts to his loyalty to the Mafia. Popularity was never high on his mind. In fact Cohn stated as much: “The worse the adjectives, the better it is for business.” Forever pulling levers and introducing people and cultivating power, Cohn’s life was concerned only with his belief that he was winning.

In the end, while he had always kept star-studded company, Cohn was ultimately left with few friends. He had powerful friends at various times – the Mafia, Reagan, Trump, Rupert Murdoch – but many were quick to desert him when his currency had waned. His reputation was built on fear and influence, and when he was disbarred no-one would go to his Thanksgiving party. That he would ultimately die of AIDS, denying that diagnosis until his death, only leaves a note of confusion at how a man could live a life so contradictory to his reality.

In the end, while he had always kept star-studded company, Cohn was ultimately left with few friends. He had powerful friends at various times – the Mafia, Reagan, Trump, Rupert Murdoch – but many were quick to desert him when his currency had waned. His reputation was built on fear and influence, and when he was disbarred no-one would go to his Thanksgiving party. That he would ultimately die of AIDS, denying that diagnosis until his death, only leaves a note of confusion at how a man could live a life so contradictory to his reality.

Tyrnauer makes a good effort in trying to find what was responsible for the creation of someone like Roy. Some interviewees point to a doting mother, whose attempt to make her son more beautiful left him with a permanently scarred nose. Some point to his father, who regularly dined with the presidential class, fostering a too-early taste for power. That he was “an evil produced by certain parts of the American culture” is the last and most resonant assessment, however, considering how long his conduct was tolerated and indeed encouraged. As an ‘ugly’ and ‘charismatic’ man, naturally he thrived in an elite environment that rewarded charisma over truth.

This feeds into the third part of Tyrnauer’s profile of Cohn, which is his mentoring of a young Donald Trump. It is said of Cohn that “Power in the hands of someone that arrogant and that reckless is a very dangerous thing”. It is a statement that could easily be said of Trump as well, and Where’s My Roy Cohn? is happy to let that parallel fester. Cohn thrived on attacking the vulnerability of others, viewing the law not through the prism of justice but of winners and losers, where discrediting your opponent is the first step to success. With that mantra Cohn might also neatly fit into a discussion of a number of other high-profile power-brokers who have been grounded in recent years for abuses of power, but the focus on Cohn and Trump’s closeness in the early days of Trump’s empire is pointed.

This approach of telling one man’s story to condemn another may not be to everybody’s liking. Certainly 97 minutes doesn’t seem enough time to weigh up the cost of Cohn’s influence on the current political discourse and rules of engagement. But that said, Cohn’s inspiration for Donald Trump’s talents and tactics to this day is plain to see and Tyrnauer’s point is well made: to understand that Cohn was an idol to Trump is to understand that Cohn’s seemingly bottomless amorality lives on in current White House practice. And that is a scary thought.

Where’s My Roy Cohn? screened as part of the Jewish International Film Festival and has an exclusive season at Cinema Nova from 5th December through Sony Pictures.