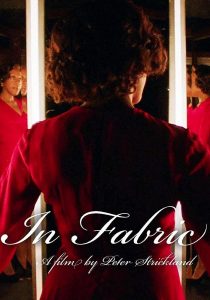

If the Bourke Street Myer windows at Christmas were given over to the control of director Peter Strickland, you probably wouldn’t be taking your children along. Imagine the people of Melbourne peering in through the doors before opening hours to see a gaunt old man on his knees surrounded by a cackle of vampiric saleswomen, all coiffed and grinning, beckoning to the masses to partake in the hedonistic ritual of ‘The Sales’. Such is the opening impression of the London boutique Dentley and Soper’s, a retailer of couture modelled on mannequins so haunted in appearance you’d expect nothing less than for a dress on sale to be the devil incarnate. This is the world of In Fabric, and it’s gloriously absurd.

Poor Sheila (Marianne Jean-Baptiste). She is just there for something to wear to a date. Single in her 50s and living with her adult son (Jaygann Ayeh), Sheila is not happy. She’s lonely. Her double-act bosses (Steve Oram and Julian Barratt) hide behind smiling, sympathetic faces as they chastise her for trivial non-issues, from suspiciously long toilet breaks to unauthorised waves. Her son’s intimidating girlfriend (Gwendoline Christie) has all but moved in and bullies her in her own house. With all this going on, the fact that the ‘artery red’ dress at Soper’s fits despite it being a 36 seems like a stroke of luck.

With the extravagant and heavily Eastern European-inflected words of head saleswoman Ms Luckmore (a scene-stealing Fatma Mohamed) urging her on—“The hesitation in your voice is soon to be an echo in the recesses of the spheres of retail”—she will soon know that the dress comes with a catch. As Ms Luckmore clambers into a dumbwaiter and descends into the bowels of her department store to dismantle her wig and fornicate with bleeding mannequins, the dress starts down its own wicked path, unleashed upon the world.

With the extravagant and heavily Eastern European-inflected words of head saleswoman Ms Luckmore (a scene-stealing Fatma Mohamed) urging her on—“The hesitation in your voice is soon to be an echo in the recesses of the spheres of retail”—she will soon know that the dress comes with a catch. As Ms Luckmore clambers into a dumbwaiter and descends into the bowels of her department store to dismantle her wig and fornicate with bleeding mannequins, the dress starts down its own wicked path, unleashed upon the world.

When you’re told that the catalogue model for the dress you are buying died, you might be sceptical. When you contract a rash after wearing it, you should be concerned at least. But when a washing machine self-destructs and leaves your hand bloodied and trembling but the dress luxurious and intact, you know it’s gotta go. This is not a film about Sheila so much as it is about whatever the dress represents: a consistent thread linking a string of disturbing events, the devil, fetish, consumerism. This is true even when the film makes a sudden about-face at about mid-way and the focus turns to a soon-to-be-married Reg Speaks (Leo Bill), a sullen washing machine repairman who has the ability to entrance people with technical jargon, and his fiancé Babs (Hayley Squires).

Strickland employs an enjoyable blend of the disquieting and the laughable in giving In Fabric a hallucinogenic or dreamlike quality. A dress slips across the floor, televisions splutter to life with hypnotic graphic variations of the word ‘sale’ and rotating mannequins and patrons stream through a shop with an excitement beyond their control, saleswomen clapping at their heels. A cinema tragic might call to mind the horror films of the 1970s or works like Suspiria that draw more from eeriness and warped desires than scares. For someone not wanting to get so bogged down in the history of cinema, what springs to mind is Homer Simpson buying a cursed Krusty doll. Of course this could never be considered a criticism.

Although In Fabric does recycle a number of tropes from comedies and horrors past (cursed objects are nothing new), Strickland’s absurdist and grimly fetishistic imagination makes In Fabric far too strange to be termed a parody or a tribute. The thrumming retro soundtrack by Caverns of Anti-Matter matches Strickland’s weirdness, and it is perhaps indicative that as events unfold a demon baby giving the middle finger in a dream sequence doesn’t seem out of place. It’s merely unnerving, and it’s part of why In Fabric is a must-see and why I’d like to see what he could do with a window display.

In Fabric is in cinemas from 12th March through Arcadia.