‘If there’s no one there, no one cares.’

‘If there’s no one there, no one cares.’

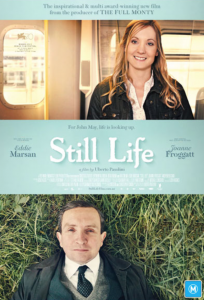

It’s the kind of flippant remark from the new council manager that case worker John May (Eddie Marsan) can’t stomach. This is because he is there, and he does care. Uberto Pasolini’s latest film, Still Life, takes a gentle trajectory in delving into the life of this insular man.

For years, John has worked for the local council, painstakingly seeking out the relatives of people who have died alone. He does this out of a belief that every person’s story, however unremarkable, deserves a fitting exit. He arranges and attends their funerals, writes their eulogies when no one else can, and reserves a special folder in his featureless home for the many lifetimes of photos and memories that were never claimed.

When the council signals a round of cutbacks, the new manager (Andrew Buchan) makes May’s role redundant, and he is given notice that his current case will also be his last. This just so happens to be the case of a man who died alone in the squalor of the apartment opposite John’s own, putting May’s own solitude into sharp perspective.

The overriding themes coming from this restrained tale of self-discovery are the importance of family and the mark you leave behind on the world. That writer-director Pasolini opts to demonstrate this through the eyes of an overly unremarkable man who has no family makes for an interesting standpoint.

For those who’ve ever read Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day, there are shades of the old stalwart being forced into a re-evaluation of his life’s achievements. Like the main character in that book, our hero here, who for so long has acted primarily as a catalyst for fulfilling the wishes of other people, is forced to contemplate what his own life is worth when his major purpose is taken away.

It stands to reason that this film is most interesting – and its message most effective – from the point when May realises that his duty to the dead has been at the expense of having a life of his own. Principal in this realisation is an encounter with Kelly (Joanne Froggatt), the troubled daughter of one of his last case. It’s a moving, if hesitant, relationship. Importantly, it makes up for a slow beginning, which at times over-eggs John’s stale existence – a set-up that establishes him as less a person than purely a symbolic vessel for Pasolini’s sentiments. Some contrivances in the conclusion unfortunately reinforce that view.

However, there is no denying that the sentiments are noble and the performances strong, making this small piece of melancholy ample food for thought.

Still Life is in Australian cinemas from July 24 through Palace Films.