Media has a tendency to be predictable, safe fare. For all your superhero flicks and CGI End Of World scenarios, you always know by the end of the movie that the goodies will have triumphed against (insert bad guy here). It’s comparatively rare for a movie or show to break this unwritten contract with the audience.

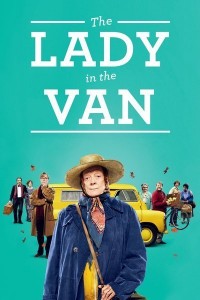

But every so often something comes along which shocks the system. The opening to The Lady in the Van is about as unexpected as you can get; a terrified scream and a thump which you can pretty much assume is fatal. As the story opens, we find it’s Maggie Smith behind the wheel of a vehicle with a red stained smashed windscreen, and it’s pretty obvious something awful has happened. That she’s being pursued by a black maria – a police car – further complicates her life. She gives policeman, Jim Broadbent the slip, but it’s not going to last. And yet…

In twee 1970s England, she reappears as Miss Shepherd, a homeless woman shifting the very same van from street to street, and getting crabby with anyone who plays music. To put it mildly, she is a cantankerous old bat. The upper middle class citizens of North London object to her presence, but being British, they don’t object too harshly because that wouldn’t be becoming. It’s left to Alex Jennings as playwright Alan Bennett (who wrote the stage play the movie is based upon, as well as the screenplay) to show a little compassion. But is he being compassionate, or – as he puts it in his conversations with his imaginary twin – just cowardly?

The scenes where Alan is talking to himself are quite well directed; there’s Alan the writer, and Alan the home owner. The latter deals with Miss Shepherd, while the former writes about his experiences. They talk to each other like an old married couple.

There’s very little difference these days between many cinema and TV productions, and Nicholas Hynter as director could very well have crafted this movie as a three part BBC drama (in fact the movie is produced by BBC Films). And yet, like the excellent job the crew performed for the astonishingly slow moving Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, production designer John Beard, set decorator Niamh Coulter and art director Tim Blake seem to have captured the sense of lost opportunity that the 1970s represented. That is, the upwardly mobile throwing out the reminders of the past (which would be snapped up in a heartbeat by modern hipsters), the muted colours and the sense of opportunities lost since the baby boom of the 1950s and the swinging 60s.

This sense of hopelessness and regret seems written deep into the story’s DNA and if not for the eccentricities of the leads, would make the movie a real slog. Alan sees something in Miss Shepherd, and despite her self-imposed isolation, acts as her unacknowledged guardian. As the story progresses, we slowly learn more about Miss Shepherd and Alan; both are loners and seem, despite outward antagonism, to need each other.

The Lady in the Van is a story firstly about people’s relationships. It starts as a drama with the death of a motorcyclist, and moves through the interaction between people. It’s a well rounded tale of tragedy and fear, with liberal doses of self-doubt but finally redemption and perhaps even rebirth. If it were a book it would be filed under “Literature”. Not that the marketers at Sony and BBC Films would have you believe that. They’ve packaged the movie as a jaunty comedy featuring James Corden who actually appears in the movie for all of thirty seconds. And it’s this kind of lazy marketing which really misrepresents the movie and ultimately does the story a disservice. Yes, get bums on seats, but how about doing it by actually marketing the movie, not a bunch of humorous cut scenes?

The Lady in the Van is in cinemas from 3rd March through Sony Pictures.