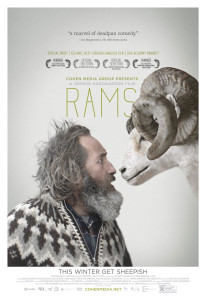

Rams, written and directed by Grímur Hákonarson, opens with a wide, panning shot of a farmer tending to his sheep. It could almost pass for a landscape painting; despite being set in the present, there is a sense of picturesque nostalgia infused in it. Winning the Un Certain Regard section at the 2015 Cannes Film Festival, this Icelandic film about two estranged brothers living in the pastures of northern Iceland is filled with lovely, restrained imagery, and explores their attempts to deal with threats that undermine their generations-long livelihoods.

Quiet and thoughtful Gummi (Sigurður Sigurjónsson) is the farmer of the opening scene. He lives next door to his more volatile brother Kiddi (Theodór Júlíusson). They have not spoken in forty years (the reasons why remain unexplained), and have no wives or children of their own. Instead, they have cultivated their closest relationships with their prizewinning flocks of sheep, which have been passed on for generations and are the primary source of income for the region. When scrapie disease hits Kiddi’s flock there are grave concerns for all of the sheep in the region, and the farmers are compelled to exterminate their flocks and wait a few years until they can begin again. However, not all of the farmers can afford to wait that long. Gummi and Kiddi each respond in contrasting ways, and the hardship which threatens their way of life forces them to re-evaluate their decades-long falling out.

There is a meditative elegance to the cinematography, a warmth in the muted colour palettes of Iceland’s rocky, windswept countryside and wintery landscapes, that makes the scenery beautifully calm and subtly arresting. Hákonarson’s compassion is evident in scenes of the brothers and other farmers amiably tending to their sheep and later, to the progressive development of a new stage in the brothers’ relationship. He achieves this with little to no score (and what score is included is wonderfully understated) and steady, prolonged shots, both of which evoke a sense of serenity. As the film unfolds there is also a tender sadness to the ways in which Hákonarson presents these livelihoods at stake, and the muted, withdrawn anguish that the farmers experience at the prospect of an uncertain and lonely, future. However, there is also a surprising, endearing humour that importantly complements – rather than jars against – the film’s overall gentle melancholy. The pacing is a little slow and pensive at times, and this requires a sustained alertness and patience, but the film would probably not have the same cumulative impact any other way. Rams unfolds at its own measured pace, one that matches its cold yet tranquil setting, and this makes the simple lyricism of the film’s final image all the more poignant.

Rams is in cinemas from 7th April through Palace Films.