The biopic film has been around for many years. Its first appearance in the cinematic realm was Joan of Arc by film pioneer Georges Méliès. Since then, the genre has chugged along through the decades. When the 21st century hit us, the biopic seemed to become more pervasive, representing a greater proportion of feature films released than before. In 2010 alone, there were roughly fifty films released that could be characterised as biopics.

One pertinent reason for the increased emergence of the genre is attributable to its profitability. As the biopic typically tells the story of a famous or historical figure, they easily attract moviegoers. Armed with good marketing, biopic films are a pretty safe bet for investors and studios. In 2010, The King’s Speech made 414.2 million USD and The Social Network couped 224.9 million USD.

Most biopics are designed as mainstream films. In other words, they are made by Hollywood in a conventional, unadventurous way in order to appeal to the widest possible audience. This seems seriously paradoxical, considering the fact that biopics usually depict unconventional, adventurous figures. Alas, they typically feature A-list Hollywood stars, melodramatic yet manufactured orchestral music, still and controlled cinematography, and narratives that span over the life of the subject of the film.

The stated aims of most biopics are to offer an account of a person’s life, and to generate emotional and psychological responses to that in the audience. However, as the structural elements of the biopic become more familiar, the less impact these films have on us. Unique, captivating stories are condensed into a formulaic setup that drains all meaning and resonance out of them.

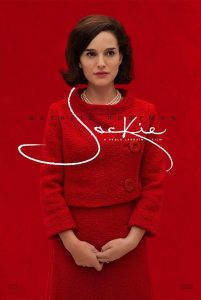

Thankfully, Pablo Larraín’s Jackie has just hit our screens. The film begins days after JFK’s assassination, in a big, white but empty mansion. Jackie Kennedy (Natalie Portman) is being interviewed by Life Magazine journalist Theodore H. White (Billy Crudup). The film commences with a close-up of Kennedy’s contemplative countenance, with the evening skies glowing in the background. The scattered narrative structure means that the film jumps between the interview and Jackie’s immediate experience after JFK’s death – organising his funeral, meeting with the Johnsons, and consulting a sagacious priest (John Hurt).

The narrative structure of Jackie is divergent from the typical biopic formula. While many (if not most) biopics feature flashbacks and flash-forwards, the narrative of Jackie is so fluid as to distance itself from the kind that is usually delivered. Noah Oppenheim’s script, in organising the action of this film in this way, does so with a purpose. That purpose is to convey the overwhelming psychological toll that was imposed on Jackie. This does not only emanate from the visceral horror of witnessing her husband’s grisly death, but also from the pressures of being the First Lady and the uncertainty of position and status that accompanies prominent women in the ‘60s. The sense of meaningless and fragmentation that is constantly being referred to in Jackie is deftly captured through its narrative structure.

The typical biopic narrative charts some major event in the life of the subject of the film, concluding on a meaningful, closed note. Jackie does not necessarily do this. Notwithstanding that it deals heavily with JFK’s assassination, the film’s narrative is loose and confined. Rather than featuring a preordained, rigid set of events, it feels like Jackie is more so shaped by organic, private moments. This is a move that pays dividends for Larraín’s film, as it permits the examination of Jackie’s psyche and her bouts of hopelessness and grief. In this respect, the narrative provides fertile ground for the themes of womanhood, uncertainty, bereavement and American identity to present themselves in the forefront of the film. The minimalist narrative ensures that Jackie is not overwhelmed by sterile narrative strands, instead preferring to allow the film to steer itself in a more scene-by-scene, exploratory direction.

The cinematography, helmed by Stéphane Fontaine, is arguably even more integral in moulding Jackie as a psychodrama than the narrative itself. As soon as the film begins, we recognise that it is not going to be a standard biopic – the camera stands invasively in Jackie’s face, and at the same time seemingly probes her psychological processes. Behind her is a colourful, peaceful sky. The shot looks more Malickian than biopic.

Fontaine’s camera does not cease behaving in this way. Throughout the film, it unremittingly invades the personal spaces of Kennedy, providing an array of extreme close-ups. It reinforces the idea that Kennedy is the sole subject of our interests, and aids Larraín in concentrating on her psychological experiences following the fated day. At a basic level, it even allows us greater access to her facial expressions, thereby clarifying further her thoughts and feelings at any given time.

A particular highlight of Fontaine’s cinematography is when the camera follows Kennedy through the hallways of the JFK-less White House. Maintaining its distance, and observing the unlit, capacious hallways, the camera renders Jackie a slim, shadowy figure. She is cloaked in the darkness of the hallways, almost without a tangible presence. This piece of camerawork and lighting is remarkably insightful, and perfectly captures Jackie’s sense of impending irrelevance, loneliness and nihilism.

Alongside many of Fontaine’s immersive shots is Mica Levi‘s score. The music featured in Jackie is so accomplished that it is difficult to encapsulate in words. Perhaps the best word to describe it is haunting. Discrepant to, and darker than the score of conventional biopics, Levi’s music affords the film another level of psychological and emotional insight. The discordant, elongated use of string instruments instills an intangible anxiety in us. The most important effect it has, though, is in reflecting Jackie’s internal life.

Certainly, in combining these three elements of filmmaking – narrative, cinematography and music – it is impossible not to conclude that Jackie is more comfortable as an avant-garde film than an ordinary biopic. And surely it is much better for that.

The artistic sensibility of the film makes one thing clear. That the studio producing it did not hold creative control, but that its director, Pablo Larraín, did. He is a Chilean director, known for foreign political films. Perhaps No is his most well-regarded, set in Pinochet’s Chile. That he would direct a film about one of America’s most famous historical figures is strange, as that privilege is usually reserved for American directors themselves. It is almost an unwritten rule that that happens. In bucking that trend, though, Larraín’s Jackie thrives in a way that it would not have otherwise. Larraín’s artistic, mulling style of filmmaking befits the kind of film that needed to be made about Jackie Kennedy. That is, Larraín was able to create a film that was deeply engaged in the psyche and character of Jackie. Therefore, Jackie is a personal, affecting film that permits us to read into Jackie Kennedy’s human experiences. Beyond that, it permits us to read into fundamental ideas and feelings of human nature itself.

Jackie is in cinemas from 12th January through Entertainment One. Read our review here.