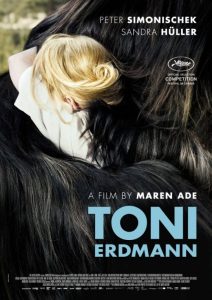

Toni Erdmann may be the funniest film to hit cinemas in a long time. Its 162-minute runtime is peppered with inappropriate, kinetic jokes and quirks that never fail in their ability to satisfy our inner humourist. One of the more comic sequences in the film is when Winfried Conradi (Peter Simonischek), wearing a big, clownish suit, and sporting a ridiculous implausible wig, confronts his daughter Ines (Sandra Hüller) and her friends at a bar. Winfried introduces himself as Toni Erdmann, a successful European life coach. Ines is, as one would expect, irritated by her father’s strangeness. Nonetheless, she plays along with him, unwilling to out him and in the process embarrass herself.

Ines is an ambitious businesswoman. She works as a consultant in Romania for a profitable oil company. Her responsibility is to advise the CEO of the company, Henneberg (Michael Wittenborn), on how to best outsource services so the company can increase profit. Ines says that she is probably in the position mainly to be blamed for the outsourcing (‘they can blame it on the consultants’). None of this seems to bother Ines, who is only intent on climbing up the corporate ladder.

Her father, Winfried, could not be more different. A divorced drama teacher in a rural school, Winfried saves himself from boredom and loneliness by adopting absurd alter-egos and performing practical jokes. After his beloved dog dies, Winfried travels to Romania to stay with his daughter.

As soon as they first meet just outside her workplace, we see why they haven’t got along so well. Ines is uptight, reluctant and guarded. Winfried is inviting, amusing and outgoing. Ines is always busy, Winfried always has free time. It is obvious that Ines is more interested in her work than in spending time with her father. This isn’t necessarily because she is in love with her work, but because of how much she doesn’t want to interact with Winfried.

And that raises an important point. Ines is so dedicated to her work because she has nothing else. Without her work, and her rigid ideas of corporate success, she doesn’t have a whole lot. No real hobbies, no friends and a distant family. Director and writer Maren Ade makes a melancholic point out of Ines’s emptiness- as her work life is portrayed as toxic, unfulfilling and exploitative. In a scene about midway through the film, Ines’s sexual encounter with a co-worker (Trystan Pütter) is unenjoyable, forced and almost procedural.

Similarly, Winfried’s practical jokes probably emanate from a place of longing. He is also without much in his life, and he fills that gap with surface humour. Although Winfried and Ines seem polar opposites, perhaps they have more in common than first thought.

Ade’s screenplay is exceptional. It is long, but it always justifies its length by offering us greater development of the two main characters and new truths about human existence. It feels like it is even elevated courtesy of the performances delivered by Hüller and Simonischek. Hüller adds real human complexity to Ines, who could have come off as a one-dimensional corporate stooge with a less talented actress in the role. Likewise, Simonischek’s sense of timing, and his oscillations between moments of private pain and imposing practical jokes is human and truly memorable.

Probably the greatest strength of Toni Erdmann, amongst its array of them, is that it combines and layers comedy with sadness. One of the final moments of the film, which should not be spoiled, represents the perfect marriage of these two things. On the surface, we are lavished in the absurd preposterousness of what we are seeing. Buried beneath is an expression of tiredness with the meaningless nature of corporate work, and the freedom associated with rekindling important familial bonds.

Toni Erdmann is a confident assertion of the talents of its three main players: Ade, Simonischek and Hüller. It is sure to stand the test of time, and become one of the more cherished German films of recent memory. In the short term, though, it is bound to be a contender for one of the best foreign films of 2016, battling against the psychosexual drama Elle and the equally-confronting The Handmaiden.

Toni Erdmann is in cinemas from 9th February through Madman Films.