One of the many things that seem indispensable to the Russian identity is its writers. As the adage goes Russia is the world’s most reading nation – partly due to their beautiful language and partly because of how long their novels seem to be. With Dostoyevsky, Pushkin, Nabokov and of course the father of them all Leo Tolstoy, it’s a culture that seems to cultivate great literature and none more so than in it’s foremost playwright Anton Chekhov.

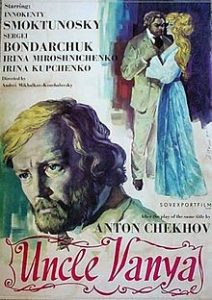

Playing as part of this year’s Russian Resurrection Film Festival is Andrei Konchalovsky‘s 1970 adaption of Uncle Vayna. Professor Serebryakov (Vladimir Zeldin) has recently retired after a lifetime of academia and is looking forward to a quiet visit to the country with his much younger second wife (Irina Miroshnichenko). He visits the estate of his deceased first wife and in the process opens up some unresolved tension that still lingers. His brother-in-law from his first marriage, the ‘Uncle Vanya’ of the title (Innokenti Smoktunovsky) has worked on the farm for years and hardly turned a profit because most of it is sent to the professor. With years of built up resentment, fighting and backstabbing soon begin.

This is a very beautiful and, for better and for worse, an unmistakeably Russian film. Chekhov is one of the most melancholy writers that this spacious land ever produced, always creating experiences that challenge and explore the notion of human sadness. Vanya is classic Chekhov: a thoroughly forlorn story about people with lives of disappointment and heartbreak – a “theatre of mood” it’s sometimes called.

It’s not that easy to follow at first; there are quite a few characters stuffed into a small space and it’s quintessentially Russian with a slow pace and roaming story. Plus, without knowledge of the source material it’s hard to figure out who is who as there are a lot of implied connections, and when it comes to names the Russians aren’t exactly thrifty with their syllables. Yet this is indicative of both the author and the culture it came from. Soviet cinema is the adverse of everything people in the West grew up with – it’s not meant to be penetrable at first; you have to do a lot of the work yourself.

It is the mature discussions and wonderfully stoic feel that makes the film stand out. The entire cast are classically Russian – serious men and strikingly beautiful women, all of whom bring the sadness and grace of these characters to life. Many of these were on the A-list of the Soviet film industry, bringing with them a seriousness that characterises the USSR’s film culture. A lot of the mood is due to the cinematography; every shot seems considered and the camera only moves when necessary.

“Maybe the people in the future will find out how to be happy” laments Vanya in the closing scene. It’s the sense of tragic melancholy which brings out the true value of this film; Chekhov’s sad characters and his compassionate treatment of them seems like a good match with Konchalovsky’s sparse way of filmmaking. You have to be patient with Russian films and this is no exception, but stick with it and you’ll find a beautifully shot film with sorrow in its heart but a will of stoic strength.

Uncle Vanya screens as part of the Russian Resurrection Film Festival 9th to 19th November at ACMI.