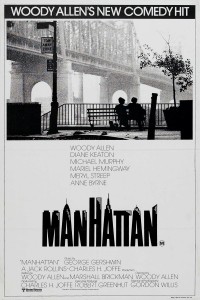

Many have named Manhattan Woody Allen’s greatest film; some, the greatest film of all time. Allen himself was reportedly so disappointed with it that he attempted to convince United Artists to never allow it to see the light of day. The truth, as is often the case, can be found somewhere between these extremes.

Many have named Manhattan Woody Allen’s greatest film; some, the greatest film of all time. Allen himself was reportedly so disappointed with it that he attempted to convince United Artists to never allow it to see the light of day. The truth, as is often the case, can be found somewhere between these extremes.

Never one to be predictable, Allen followed the hugely successful and influential romantic comedy Annie Hall with the bleak, Bergman-esque Interiors, and Manhattan would attempt to combine poignant rumination on life and culture with his pointed satire and self-effacing comic sensibility.

Detailing the life, times and debates of 40-something Isaac Davis (Allen) and a small group of his friends and lovers, at surface level Manhattan explores how difficult life really is for a television writer living in the greatest city in the world, unable to choose between the quirky but intelligent journalist or the gorgeous 17-year-old actress. Oh, cruel fate!

The journalist is self-assured, cerebral Mary (Diane Keaton), who happens to be the mistress of Isaac’s friend Yale (Michael Murphy), and the actress is arty free-spirit Tracy (Mariel Hemingway), who displays vastly more maturity and level-headedness than Davis could ever dream of despite her young age.

Through a series of long-form conversations, often had while walking along the darkened streets of the city that never sleeps, we learn the ins and outs of their unfulfilled lives, peppered with the kind of high-brow cultural references that Allen’s characters are known for. A love-quadrangle develops, and the four main characters despair upon discovering that a W.C. Fields reference, no matter how well timed or dryly delivered, fails to mend their emotional scars.

Allen’s character is meant to act as the audience surrogate, aware of the ridiculousness of their unhappiness and always quick with a self-deprecating quip to break up the barrage of intellectualism, but the satirical nature of Allen’s dialogue is perhaps too subtle to truly subvert the dislikeability of his characters. Allen himself said that he was amazed to have gotten away with it, and it’s easy to see what he means with the luxury of 30 years of hindsight. Fittingly, the most joyful scenes of the film are those in which characters don’t speak, allowing Allen’s Chaplin influence to shine through gloriously — but such scenes, though brilliantly deft, are ultimately fleeting.

If absolutely nothing else, Manhattan is a persuasive argument in favour of the continued existence of celluloid film, which has found itself threatened by digital photography in recent years. New York City’s foggy, low-contrast streetscapes are breathtakingly captured by master cinematographer Gordon Willis, the high-grain black-and-white film stock giving wintry Manhattan a splendid warmth, and forming a pleasant contrast with the other famous “New York movie” of the 1970s, Martin Scorsese‘s Taxi Driver. New York in the 1980s was by all accounts an almighty shit-hole, but you wouldn’t know it to look at the city through Woody Allen’s eyes.

A shot of Allen and Keaton sitting on a park bench with the 59th Street Bridge rising up behind them is deservedly one of the most iconic in all of cinema, but in one of the Academy Awards’ most egregious flubs Willis remarkably garnered no Oscar nomination for his work on the film (in a category featuring the utterly forgettable Disney space adventure The Black Hole). To make the New York of the late 1970s looks this great on film certainly deserves some kind of recognition, but Willis is no stranger to not receiving recognition for his work (examples of which include the Godfather, Annie Hall and All the President’s Men). Allen, however, was nominated for his sixth Oscar (for Best Original Screenplay), and Hemingway found herself nominated for a Best Supporting Actress Oscar despite spending barely 20 minutes on screen.

A shot of Allen and Keaton sitting on a park bench with the 59th Street Bridge rising up behind them is deservedly one of the most iconic in all of cinema, but in one of the Academy Awards’ most egregious flubs Willis remarkably garnered no Oscar nomination for his work on the film (in a category featuring the utterly forgettable Disney space adventure The Black Hole). To make the New York of the late 1970s looks this great on film certainly deserves some kind of recognition, but Willis is no stranger to not receiving recognition for his work (examples of which include the Godfather, Annie Hall and All the President’s Men). Allen, however, was nominated for his sixth Oscar (for Best Original Screenplay), and Hemingway found herself nominated for a Best Supporting Actress Oscar despite spending barely 20 minutes on screen.

But regardless of its awards and accolades, Manhattan has ensconced itself as a classic and in many ways is the quintessential Woody Allen film. With its gorgeous visual style and Gershwin score it is a particular favourite for Woody Allen parodists, but despite being delightfully self-defeating and witty it is also emotionally and intellectually muddled, not entirely unlike Isaac Davis himself.

Read more entries in our Wednesdays with Woody feature!

I’m just not sure if Allen as the audience’s surrogate is as simple an assumption. If anything Allen is incredibly critical of his own over-analysis and inflated egoism (especially concerning his rationalising of his relationship with Tracy) and the finale only points at the destructive nature of a soulless and somewhat academic attitude towards life. Once again, and despite Allen’s insistance that he doesn’t put himself in his films, the film is an analyst session for Allen himself. We are meant to experience the situation through him, but the catharsis of exploring his attitudes and experiences is his alone. What I think is valuable is the reflection of our own lives up on the screen regarding the sentiment, not so much the character identification.

Loving these Wednesdays with Woodsy.

My problem with the finale is pretty much the opposite of what you’ve said, i.e. the purely academic outlook on life wasn’t damaging enough to get that message through. Woody plays both sides of the fence (just like he plays an intellectual who bristles in the presence of a “pretentious” intellectual), and therefore muddles the clarity of his central point.

Subtlety is one of Woody’s strengths, but to me it felt like he overdid the subtlety in this one.

Quit yo Manhatin’